La Maison Dorée: What I Didn't Say About the Tunisian Arab Spring

I have a recording from the night I walked a street in central Tunis almost thirteen years ago. It is a few minutes long—a mess of car horns and people chanting in Arabic, a language I don’t speak. The date is October 20, 2011, and the people are celebrating the death of Muammar Gaddafi, who ruled Libya from 1969 until he was assassinated that morning. I listened back to the recording recently and found myself struggling to untangle the scene from its density of sound, so I dug out my written notes, which clarify its other dimensions: Libyan flags waved from car windows; men braved the razor wire encircling the embassy and posted themselves at the door, singing; another man hoisted a young girl onto the roof of an SUV then clambered up behind her, each clutching a flag. He emphatically flapped his arms like a bird for the girl to mirror him, but instead she planted her flag and twirled around it, as though its rod were an axis.

I came to Tunisia to report two stories, one of which I never wrote. The article I would publish was a profile of a young conflict photographer, Trevor Snapp, for my college alumni magazine. I was a year out of school, mired in debt but determined to become a writer, and I contributed regularly to the magazine in an arrangement I had come to think of as a sort of personalized loan-forgiveness program. I had planned to meet Trevor in Mexico City, but then the Arab Spring arrived, the Tunisian dictator, Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, was ousted, and the nation arranged to hold its first democratic election. Trevor wanted to document the election and suggested I meet him there instead. Then, uncomfortable with the thought that I would come all the way to Tunisia to write about him, when together we would be witnessing an important historical event, he suggested that we collaborate on a story. That story, on the election, is the one I would never publish.

We met at a café on my first day in Tunis and melted sugar cubes into amber glasses of tea as he told me about Ennahda, an Islamist party which had borne the brunt of Ben Ali’s persecutions and now was leading in the polls. We agreed there seemed to be some dissonance between the fact that the revolution—prompted by a fruit seller’s self-immolation—had taken hold amid outraged university students, and that an upshot of the revolution was the runaway popularity of a party that defined itself religiously. Or perhaps it was only dissonant to Western minds like ours, and Ennahda embodied a novel take on Islamist governance not at all at odds with democracy. “The country has never had the opportunity to build a democratic government before,” I wrote in my notes. “But doing so means creating a modern Islamic identity in Tunisia that’s palatable to both the secular Tunisian and the conservative Muslim.”

Trevor would take photographs as he had planned to do all along, while I would accompany him, and together we would conduct interviews about the election. I remember feeling what Trevor was offering me was generous, as I spoke neither Arabic nor French, and he would have to do the asking for both of us. I was painfully aware that I had published only a few times in magazines before, and never about a nation other than my own, so I suspected that my odds of placing the story were low. Still, I was grateful for the task, which for each of us was perhaps a deflection: Trevor could imagine me more his collaborator than profiler, and I could imagine myself a foreign correspondent, with real reason to be in this place at this time.

The election for Tunisia’s first democratic congress began the day after I arrived. In the morning, Trevor met me in the lobby of the hotel where he had arranged for me to stay, and together we set out by taxi to Bab Souika, a neighborhood and Ennahda stronghold, to visit one of the many polling stations scattered throughout the city. There, we met up with Boukhari, an Ennahda field organizer. It was impossible to tell Boukhari’s age, though he seemed very youthful from the manner in which his legs kicked out to the sides as he walked, his slight torso swaying jauntily. He led us past fruit vendors, past whole plucked chickens and the hindquarters of animals, and when a pear rolled off a cart, he turned on his heels, despite his apparent rush, plucked the pear from the street, and repositioned it precisely on the vendor’s pile.

The polling station he led us to was in a school. As soon as we arrived, Trevor disappeared into the throng of voters as I lingered uncertainly outside the door. I noticed a young man in Ray Ban-like sunglasses and fitted jeans arriving to vote. As I had guessed, he spoke fluent English, though he was hesitant to reveal whom he was voting for. “We all know who everyone is voting for,” he said. Did this mean he favored Ennahda, I asked? He laughed and said no; he was voting for Ettakatol, a social democratic party led by a radiologist, Mustapha Ben Jafar. I asked why he thought Ennahda was so popular, and he pointed to the line growing in front of him. “The people who vote for Ennahda are very old,” he said.

Later, Boukhari would tell me that many in Bab Souika had supported Ettakatol until Jafar was rumored to be running on a “freedom of sexuality” platform, and they shifted their allegiance to Ennahda. Boukhari still liked Jafar, though. “He is good,” he said twice, as if to assure me. In any case, it would soon seem that what the man in fitted jeans had said about Ennahda voters was untrue. Many young people favored the party. Over the following days, we would accompany Boukhari to calls to prayer, to rallies, and, one afternoon, to a café in Bab Souika where I chatted with two women, friends of Boukhari’s, both in their mid-twenties. Neither wore a headscarf. One of them, Nadia, told me that she had first learned of Ennahda from her father, and over time, she had become convinced the party was the one that could best uphold the identity of her country. “Tunisia is first Tunisian, then Arabic, then Muslim,” she said. Modernity, Nadia believed, was not at all at odds with Islam, as some critics of Ennahda would have it. “To know my religion, I don’t have to go into the past. I can live it in the present.”

I had forgotten this conversation until recently, when I reread my notes. I do remember that, in my conversations with voters, I felt a queasy disorientation. Did their perceptions of Ennahda align with how the party presented itself? And what did the party represent, really? It claimed Islamism and democracy were not just compatible but complimentary, but what did it think of Sharia law? (What was Sharia law?) Would the party, once in power, privilege religion over democracy at the expense of the rights of women and others whom a conservative interpretation of the Koran might restrict? I see now that many European and American journalists were asking these same questions, in service to a readership already suspect of mixing religion with politics and perhaps oblivious to how religion and politics had already mixed to lay the foundation of their own democracies. But at the time, I felt overwhelmed by these questions, burdened by my own ignorance.

I took copious notes for this story I never wrote. When I read them now, I feel admiration for my diligence as a younger reporter, but also pity, so lost was I in unfamiliar territory that I seemed to have believed that by recording all of the detail I would eventually discern a pattern that told a story. It is easier to see that pattern now, not just because I have been a reporter longer, but because enough time has passed that I have seen the story play out. I know now who won, who remained true to their word, who rebelled, whose vision lasted and whose faltered. From the present, it is easier to see what was important about the past.

I also find it odd, as I reread these notes, how I remember so little of them. How can this be? I write things down to remember. I can recite whole paragraphs of stories I composed years ago. But it has occurred to me that perhaps it is in the translation of observation into story that memories form. And so it would make sense that what I recall most vividly from my time in Tunisia is something which I can find only a brief mention of in my notes—the hotel where I stayed: La Maison Dorée.

*

It was so unremarkable that I wonder now how Trevor found it. He probably told me; I suspect one of the journalists with whom he was staying had recommended it. It was in a French colonial corridor not far from the city center, a pale façade with no windows that I can recall, except for a tiny portal to the side of the door. The concierge would slide the portal open if it was after hours and if the door, which opened onto the tiled floor of the lobby, had already closed. The concierge did not speak English, so Trevor helped me check in. After that, I hardly uttered a word inside the hotel, except for small greetings in French whenever I traversed the lobby. I vaguely recall the décor: red and gold, fleur de lis. The walls, once cream, had yellowed. My room looked out on rooftops behind the hotel, on plants creeping across chipped patios and laundry strung up to dry.

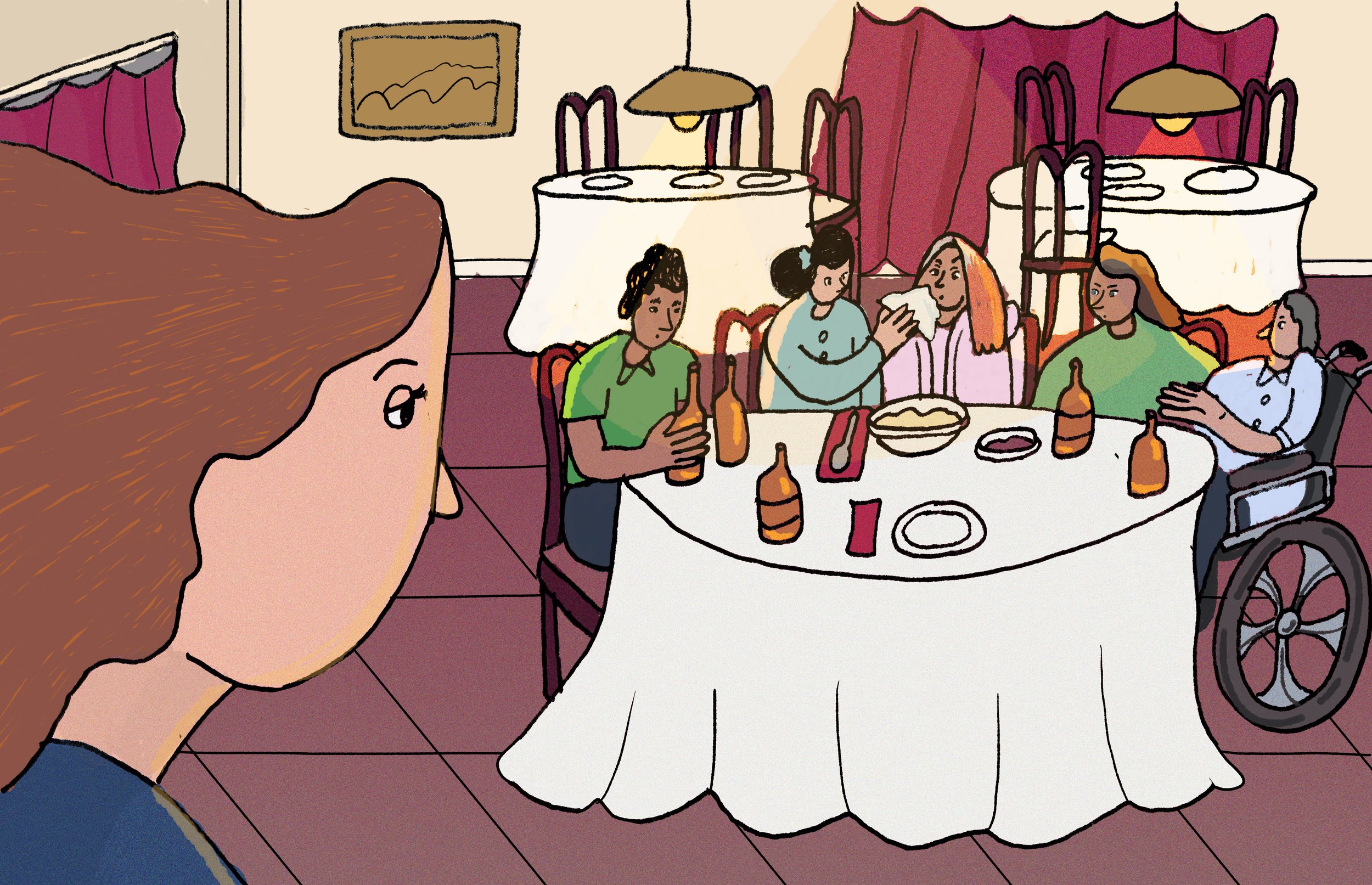

It was the dining room where I spent the most time. There, on my first evening, I found five guests seated around a table, smoking cigarettes and drinking beer. I noted a few characteristics of each guest: Vason was the first who motioned for me to join them. He was blind, in a wheelchair, with a mild case of cerebral palsy, and when I asked what he did for a living, he replied ethereally, with a flick of his hand, “I do not work. I am only Vason.” He lived in France but was a Tunisian citizen and had come to vote. So had the guest named Annette, her eyes encased in cerulean blue, whom I noted was a “radical liberal feminist,” though I cannot remember if she told me this herself or if I assumed it from something she said. There was another woman whose name I did not record, who I was told had been an advisor to the Libyan ambassador to France. She had ironed orange hair, white at its roots, and wore a pink snuggly. I never heard her speak, except to order lamb and orzo soup, which her attendant, the third woman at the table, spotted with a napkin as it dribbled down the diplomat’s chin.

“I spent our meals listening for words I might recognize—any clues as to what, exactly, had sutured their lives together.”

The fifth guest was the youngest, a 36-year-old Libyan revolutionary named Abdul Abdullah. He was tall, dark, with the body of a triathlete. By the time I had joined the table, he was on his third beer and gleefully tipsy. In more English than the other guests possessed, Abdul explained to me that he had escaped Libya only twelve days prior. His role in the revolt had been to deliver medical supplies to hospitals and encampments, but he had been captured and jailed for five months, and guards had put a sack over his head and administered an electric shock until he cried out, “Muammar Gaddafi is my God!” Eventually, someone in the security forces had helped Abdul and hundreds of other inmates escape across the border into Tunisia. Now that Gaddafi was dead, Abdul could return home.

I found these same five guests gathered in the dining room every night after that, and every night, I joined them at their table. Usually it was Annette or Abdul who would greet me most enthusiastically, then return to whatever story they had been telling in rapid French. Our companions punctuated these stories with loud laughter, and I spent our meals listening for words I might recognize—any clues as to what, exactly, had sutured their lives together. These were not people who, under any other circumstance, I would have expected to have found sitting around the same table. From the little I gleaned about their lives, I could assume they varied in religion and politics, and had existed in separate spheres until the revolution landed them all at once in Tunisia. And yet they acted like old friends, even with the mute diplomat. It was as though they had been planning this reunion for decades. They rested their arms on each other’s shoulders and raised their glasses for toast after toast. I had no idea what they were saluting and did not want to stall the night by asking them to explain. At the table, they never spoke to me directly or attempted to translate; it was as though they figured that, through their mere enthusiasm, I understood everything they said. Eventually, tired from straining to decipher their stories, from this accumulation of unsatiated curiosity, I would excuse myself and go to bed. They would protest briefly, then carry on.

One morning, as I composed an email in the lobby, Vason wheeled himself up beside me and blew a delicate cloud of cigarette smoke across my line of sight. He had heard my typing and now asked that I open YouTube and search the name of an American he once knew, a dancer. I did as he instructed. On my screen appeared a video of a blackened stage. A light blinked on, revealing a younger Vason in his wheelchair, and then the dancer—lithe, beautiful, a puff of brown hair—who now moved about Vason. She sat in his lap. She rearranged his limbs. He fell out of his chair reaching for her, and for a moment she entangled her body with his, then set him back in place. This is what I remember of the dance. The American had choreographed it for him, Vason said. I do not remember if I asked what became of her. Vason remained beside me as I watched, pulling mournfully on his cigarette, and it occurred to me that he had loved the American and perhaps was still in love.

The video surprised me, because until that moment it was as though the hotel guests had always lived in La Maison Dorée and never left, as though their stories were encapsulated within its walls, and the stories of how they had wound up there together belonged to other, former lives, lives to which this video also belonged.

I was similarly surprised when, one night, I returned to find Abdul at the front desk, clutching a roller bag, despondent. He told me that he had gone to the airport that morning to return to Libya, but the gate had been mobbed with other refugees seeking passage home, and a man missing an arm begged Abdul for his seat. Abdul could not refuse a man with a missing arm and would try again in the morning, he said. But the next evening, I found him back in the hotel, having given up another seat to a sickly Libyan. I don’t think he tried the following day, because that night, in the dining room, I spotted him in the company of a woman his age. When he noticed me, he grinned, lifted a glass of wine, and exclaimed, “Allahu Akbar!”

*

On my seventh day in Tunisia, Trevor rented a car, I checked out of the hotel, and with a translator, we drove south to Sidi Bouzid, where the street vendor had self-immolated months earlier, and then to Kairouan, a city we were told was the “door to Islam” in Africa. Kairouan had become a stronghold for Salafists who represented the most conservative undercurrent of Tunisia’s resurgent Islamism and who favored Sharia law. Many Salafists had abstained from the election, believing democracy contrary to their religion, but those who voted favored Ennahda. That afternoon in a palace courtyard in Kairouan, as the local election results rolled in—Ennahda won the greatest percentage of seats in the new congress—we met with an operative from one of the progressive parties. When an Ennahda leader passed by, the operative called out to him: “Please give us democracy.”

“We will give you a lot of democracy, you’ll see,” he replied. “Inshalla,” the operative said under her breath. God willing.

I had only a few more days in the country, and although I had amassed a trove of notes, I felt the article slipping even further out of my reach. In all my interviews, I had captured a breadth of opinions, ideas, and experiences, but as each story I encountered expanded my sense of the broader narrative, it had also revealed to me the questions I had yet to ask. Now, I wanted to return to all the people I had met, to interview them again, to ask them to share their stories in more detail or to explain more precisely what they had meant.

Most of all, I wished I could spend more time with two sisters I’d met in Tunis earlier that month. I’d attended an Ennahda event alone, where I met Soumaya and Yusra, the daughters of the party leader Rached Ghannouchi. In the 1980s, Ghannouchi had founded the Islamic Tendency Movement, promoting a democratic socialism anchored in Islamic values—at odds with the despotism of Ben Ali, a secularist. Ghannouchi and his followers were jailed and tortured. Upon his release in 1988, Ghannouchi went into exile in the United Kingdom, where he lived for twenty-two years with his family, until the Arab Spring. His daughter Yusra told me that her family benefited from exile “in the sense that we’ve gained a lot of knowledge of the things that come together to make a democracy work.” Yusra had worked in government in the U.K., as well as with human rights organizations. “Our parents were conscious exiles. They brought us up to be committed to community activism abroad, all the while maintaining their Tunisian roots.” What the press sometimes said of her father being more conservative than he let on was “laughable,” she said. “Since the 70s, my father has been writing about putting freedom in the center of the Islamic reform movement. There are many interpretations of Islam, and the one we endorse is one that’s committed to democracy, to human rights, including women’s rights. It tends to be people who really want to remain prisoners of their prejudices who tell you, ‘You don’t believe in democracy.’ There are people who say to my father, ‘You brought up your daughters like that as a plot to convince people that you believe in women’s rights, but you really don’t.’ It’s absurd. This is not a sneaky plot to shut down democracy. But democracy has to be embedded in local cultures. You can’t just transplant a democratic system onto another soil and expect it’s going to grow perfectly. The best examples of democracy are where it actually feeds from the culture, and that’s what the modern Islamist movement is about.”

This interview was perhaps the one that brought me closest to conceiving the article Trevor had suggested I write. “Why is Tunisia poised to successfully craft a modern Islamic identity integral to its democracy?” I noted. Then, a theory: “The coalescing of this modern identity—East meets West, exiled meets those held captive.” And a central conflict: “We must explore how secularists and marginalized Islamists (namely Salafists) fit into this identity. Or how they don’t, and why that will be problematic.”

I wished I had remembered to record the Ghannouchi sisters’ contact information. I needed a translator. I wondered if Abdul had made it home to Libya. And would the other hotel guests return to Europe, now that the votes were counted? I hoped I would make it back to the hotel before any of them left.

We slept that night in an otherwise empty hotel in Kairouan, then stayed another night after that. By the time we returned to Tunis the following evening, it was dark, and the door to La Maison Dorée was closed. I waited in the street with my luggage, knocking loudly, until the concierge slid open the tiny portal and informed me that the hotel was full.

*

I pitched the Tunisian election piece three times. Only one editor responded, kindly explaining that what I had was a “topic,” not yet a “story.” I knew that the difference between a topic and a story was key to landing a magazine assignment, and I agreed with the editor: I had an intriguing tableau of vignettes from a nation amid transition, but no clear sense for how these vignettes were related. Metaphorically, I suppose, I had happened upon some interesting people chatting around a table but lacked the ability to comprehend what they said. Besides, by the time I received my rejection, the election results were old news. If I wanted to write about Tunisia, I would have to return, perhaps several times, to let the story unfold. The question that interested me was speculative: Would this young democracy succeed? Given how little time I had spent there, I had no authority to speculate. The rejection came, admittedly, as a relief.

I wrote the profile of Trevor for the alumni magazine and filed away my notes. A week after I left Tunisia, I traveled to the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation in North Dakota, my second trip to report on a burgeoning oil boom that was sure to transform the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, the tribal community in the middle of it. I stayed there a while that fall. A woman who managed the tribe’s museum, when she learned that the casino hotel was full and that I had been sleeping in the parking lot, offered me her late sister’s house. I would return there often over the years, sometimes for months, as I reported my first cover story for a magazine, which led to other stories, and then to my first book. The more time I spent on the reservation, the more I understood the transitional moment it was in, and the more easily I could recognize an important story when it emerged. It did not occur to me then, but looking back, I see how unnerved I had been by my own ignorance in Tunisia—how much history I had missed, which was essential to understanding the political moment—and how perhaps the time I spent on Fort Berthold had been an antidote to my residual unease.

“Metaphorically, I suppose, I had happened upon some interesting people chatting around a table but lacked the ability to comprehend what they said.”

Now I see there were things even people who understood Tunisian history could not have known: In the years after the election, Tunisia would be held up as a model of democracy in the Arab world, Ennahda seemingly having succeeded in generating a real pluralism. But the country would simultaneously become a top exporter of ISIS fighters—the imprisonment of and brutality toward Islamists during the prior U.S.-backed regime having so radicalized a generation—and memories imprinted by this violence would further destabilize the Middle East. Then in 2021, the President of Tunisia, Kais Saied, whose candidacy Ennahda had supported, would dismiss the parliament and later the judiciary, revise the nascent constitution to grant himself more powers, and imprison his opposition, among them Rached Ghannouchi. Violence begets violence—I understand that. But still, it often seems impossible to know exactly how and where and by whom this violence will repeat itself.

Amid the world’s brutal moments, of which there have been a lot lately, journalism has felt to me like a survival strategy. I have always been curious about how other people live. I am the creep who passes through a neighborhood at night noticing how a family lights their home; if they cook; what art they hang on their walls; which television shows they watch in lieu of sleep. But voyeurism implies distance, and what I want is to get inside. I will never see into the future, but if I can see into the many iterations of what is within the present, I might understand what is possible, what is at risk, what is to come.

For this reason, I have rarely felt the desire to write fiction, with one exception: Whenever I recall La Maison Dorée and that mysterious collision of lives, my imagination blooms with new stories, adding endings to the ones I heard only the beginnings of, before the concierge closed that portal on me.

I imagine Abdul is still living in the hotel. Every day, he goes to the airport to fly home, and every day another person tells him a sad story, and he gives the person his seat. Imprisoned by his own generosity, he has deemed himself less deserving of returning home so many times that eventually he cannot remember why he ever wanted to, so even as the sad stories become less urgent, Abdul gives up his seat anyway.

I imagine that, one day, an older journalist arrives at the hotel and recognizes the diplomat as a longtime member of Gaddafi’s inner circle. The diplomat is in hiding, her muteness a ruse, and the guests in whom she has found companionship must contend with having befriended an aide to a dictator whose violence is the reason many fled their homelands to begin with. Annette wants to cast the diplomat out, while Abdul agonizes over what to do, and ultimately the attendant makes the decision to poison the orzo soup.

I imagine that every woman who passes through the hotel becomes the body on which Vason projects the memory of his lost love. Eventually Annette, exasperated by his melancholy, writes to the American dancer, inviting her to choreograph a show in Tunis. Vason is so inflated with hope that Annette cannot admit to him that the dancer fails to reply. So Annette learns the choreography herself and, one night, performs it in the dining room. She pulls Vason out of his chair, entangles with him, then settles him back in. She cannot satisfy him with this dance, though. She takes to dancing for herself, every night in the dining room after the others have gone to bed, and as Vason’s melancholy deepens, her joy expands.

In these fictions, I never leave the hotel. I speak French. I understand everything that is said. I close the gap between the outwardly observable and inwardly unknowable, between La Maison Dorée and the world beyond. In these fictions, the walls of the hotel become porous, and I can see where the revolution got in. Because ultimately it was the revolution that sutured our lives together, and perhaps the simplest part of the story is the truest: We were in the same hotel, at the same moment in time.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sierra Crane Murdoch is the author of Yellow Bird: Oil, Murder, and a Woman's Search for Justice in Indian Country, which was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. She has written for Harper's, This American Life, The Paris Review, VQR, The New Yorker online, and others. Her second book, Imaginary Brightness: An Autobiography of American Guilt, is forthcoming from Random House.

Read Sierra’s “Behind the Essay” interview in our newsletter.

Illustrations by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure, with thanks to guest editor Ted Conover.