About Yannis, the Champion of Champignons

While visiting a quaint, romantic village in the south of France, Jonathan Arlan hoped to practice his French. He did not expect to befriend Yannis, the resident eccentric.

You never think that your only friend in a new town will be a wild-eyed little mystic who lives in his van out past the cemetery. It just sort of happens. One minute you’re waiting for the bus, and the next you’re up to your eyeballs in talk of heavenly energies and the finer points of foraging for mushrooms. Before you know it, he’s hugging you and making plans to meet up again. Sometimes, as Yannis might say, the stars just align.

I had come to learn français and I’d given myself a month to do it. And almost as soon as the idea had occurred to me—to stay at my cousin’s appartement in a small village in the south of France—I was fantasizing about the people I’d meet and how quickly they’d fall in love with me. You lucky villagers, I thought. You will be my unwitting—and unpaid—instructeurs. You will be my friends. All I’d need to do is show up, I figured. The rest will take care of itself.

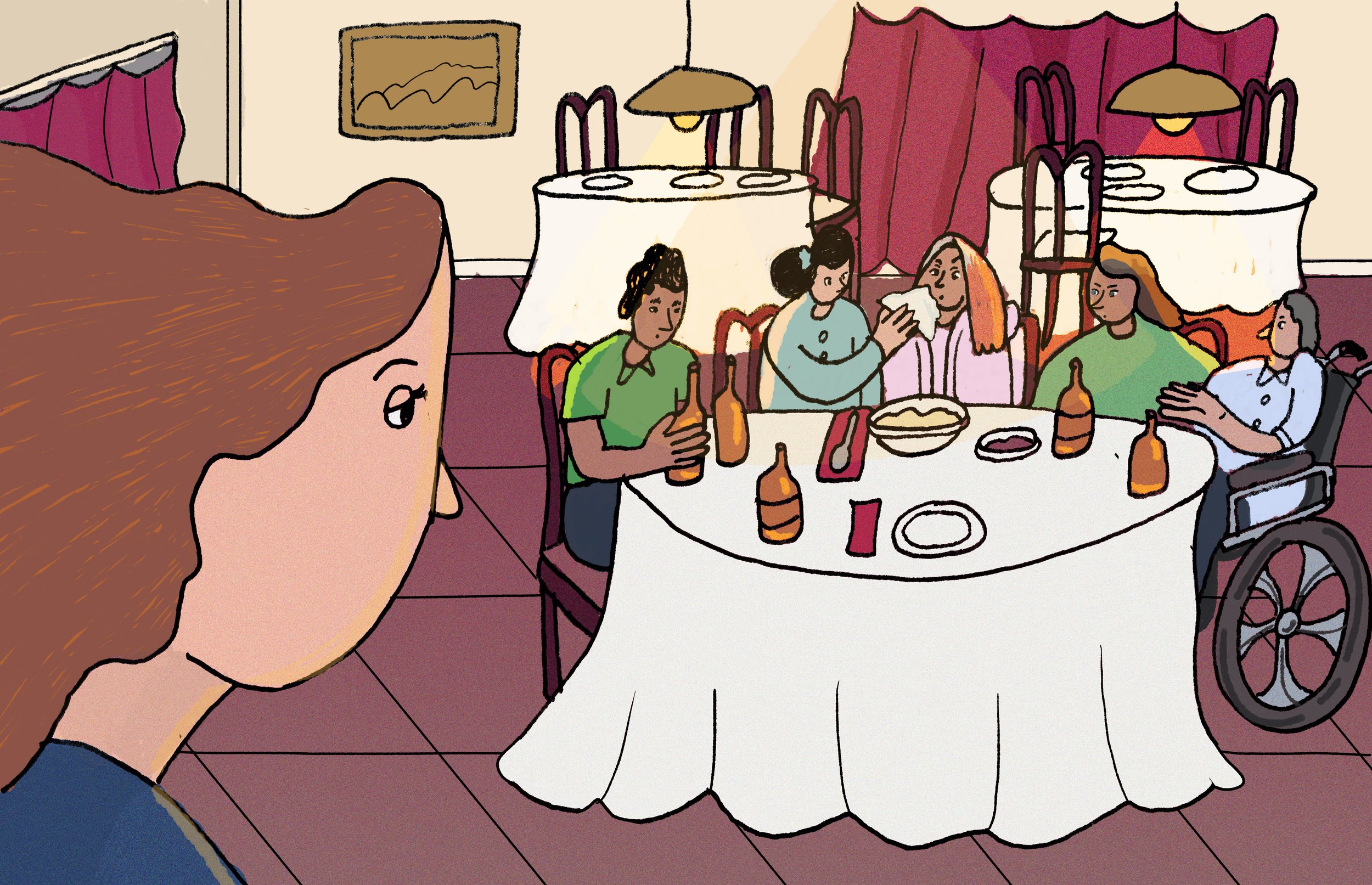

Perched seven hundred meters above the sea at the foot of the French Alps, the village is home to a café, an épicerie, a boulangerie, a small newspaper stand, a post office, views, on a clear day, all the way to Corsica, and property values in the high ninety-ninth percentile. In the center of the ville is an ancient Roman city roughly the size of a dime. It’s the kind of quaint, small town where everyone knows everyone else’s name, number, and Lamborghini. So there was no way the villagers wouldn’t notice me, a mysterious outsider with filthy sneakers, a scruffy beard, and a bus pass. There was no way they wouldn’t see me sipping noisettes at the café, or buying deux croissants daily at the boulangerie, or squeezing tomates outside the épicerie. There was no way they wouldn’t think to themselves, who is this stranger, always buying croissants and squeezing tomates in our village? And there was no way they wouldn’t invite me into their homes for those freewheeling French dinners that don’t start until eleven p.m. and only end when everyone has smoked a carton of cigarettes.

“Bonne nuit,” I’d finally say as the sun peeked over the mountains.

“Your French is remarkable,” they’d reply, only they’d say it in French.

I, for one, could not wait to meet mes nouveaux amis. With any luck, I’d be speaking French in no temps!

You can imagine my bewilderment, then, when after the first week, not a single local had struck up a conversation with me. Astonishingly, no one seemed to care who I was or what I was doing there. What’s wrong with these people? I wondered. It’s not as if poor American writers with thirty-odd words of French stop off here every day. Can’t they see what they’re missing?

So when Yannis started yammering away at me on the bus, he was both a breath of fresh air and—this really should have been a red flag—a breath of slightly less than fresh air. I usually hate when the hopelessly friendly open up to me on public transportation, but after a week of le froide shoulder française, I was pleased to have Yannis’s company. And with me in the window seat, he seemed delighted to have a captive audience.

“‘See. I told you we’d see each other again.’ This time it was creepy, as this statement can’t help but be.”

Born to a French-Greek father and Russian mother, Yannis had spent most of his forty-five years in France, but spoke all three of the family languages (plus English), frenetically, breathlessly, and to anyone with a pulse. On the bus ride alone, he got a Ukrainian yoga instructor’s phone number, cracked a joke in French to the driver, and tried to teach me a Greek proverb that had something to do with astrology. When he really got going—about the aforementioned mushrooms, for instance—his little azur eyes would sparkle and the plume of thinning grey hair atop his head would jiggle like unset meringue.

He worked summers along the Riviera as a tour guide, he told me, mostly for “rich assholes” but sometimes for “nice Russian women.” These were the two categories into which he put most of the world’s population and I think it struck him as refreshing, if not downright serendipitous, that I didn’t fit neatly into either one.

“I’m so glad we met,” he said as we approached Nice. “I feel a very strong connection to you and I know we will see each other again.” This could have sounded very creepy, and by all means, it should have. But there was a certain. . . je ne sais quoi about Yannis that gave him the sincerity of a tightly wound, if slightly embittered, puppy. Far from wanting to get away, I had to resist the urge to pet him on his fuzzy head and scratch him behind the ears.

“Me too,” I said. “Vous live in the village?”

“Well, it’s complicated, you know. I’m moving now, from Nice. And I will stay in the village for the summer. I have to go to pick up the tour van now and bring it back up. I use the van for tours. I do many tours and I need the van. For the tours, I mean.”

“Great,” I said. “So we will see each other again. It’s a small town.”

“The town is small, but it’s the universe that brought us together. And the universe is very large.”

“Oh,” I said, “OK, well, sure.” It was here that I started to wonder if Yannis might not be playing with a full deck of cartes.

The next time I saw Yannis was on a hike about a week later when he yelled my name at me from a hundred feet away. It’s disconcerting to hear your name being called in a place where no one has taken the time to learn it. It’s especially startling when it’s coming from a white cargo van parked on the side of the road.

“Yannis?”

“See. I told you we’d see each other again.” This time it was creepy, as this statement can’t help but be.

“Do you live over here?” I asked.

“Yes. Right back here.” He jerked his thumb in the direction of the valley below.

“Down the hill?”

“No, right back here. In the van.” He smiled at me as I shifted to look past him. A small mat vied for space with a pile of instant noodle cups. It smelled strongly of mushrooms. “Can you believe these rich assholes pay to live up here?” he asked me.

It seemed to me that having a bathroom under the same roof as all the other rooms was a good enough reason to pay to live, well, anywhere. And, frankly, except for the fact that no one would talk to me, everyone seemed lovely. But I don’t like arguing with people, and, technically, thanks to extremely kind cousins, I was living rent-free, too. So Yannis and I actually had that in common.

“C’est absurde,” I said. “Look at all the space in your van. Who needs more than that?”

His smile stretched even wider and it was here that I wondered if Yannis might be a bit of a psychopathe.

“Where is your house?” he asked me.

“Oh, uh, in town. Near the center.”

“Where, exactly?”

“You know, not far from the café.” I knew as soon as I said it that it was a stupid thing to say. He’d only have to stake out a half a dozen places before he’d find out where I lived. At which point, he’d climb through the window, murder me, and make himself at home in my cousin’s lovely apartment for the cost of a crowbar and some poison. Which would really stick it to these rich assholes.

The last time I saw Yannis was a few days before I left. I was turning the key to lock my door when, once again, I heard my name being called from somewhere off in the distance. When I spun around, there he was, all five and a half feet of him, across the street from my cousin’s place, grinning like a deranged marionette.

“Yannis. What are you doing here?”

“I wanted to invite you to dinner. At my place.”

“In your van? Wow. That’s really kind. But I’m leaving tonight,” I lied.

“Lunch then. We can sit at my picnic table. I picked some champignons.”

In the ten or so minutes it took us to walk past the cemetery to the picnic table next to his van, Yannis hardly drew a breath between words. I interrupted a few times en français until I understood that he just liked having someone there to listen to him. He wasn’t a psychopath. Like me, he was just a little bit lonely. Maybe he just wanted to practice his English, I thought. I could hardly blame him.

Munching on freshly stolen mushrooms, I stared out over the le méditéranéen, and let Yannis’ cosmic blathering wash over me as if it were the warm blue water itself. I smiled at my bonne chance. In the month I’d spent in the village, Yannis had provided me with more than half of the total conversation I’d had with locals. Without him, I’d probably be talking to les arbes and les animaux by now. So, sure, I’d be leaving the village with French just as awful as I’d arrived with, but I’d made a friend. He may be a bit strange, I thought, but at least he’s no étranger.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Jonathan Arlan is an editor and writer based in Kansas City. His first book, Mountain Lines: A Journey through the French Alps, was a New York Times summer reading recommendation (they kindly called it "a disarmingly engaging memoir by a millennial Kansan"). His writing has appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Literary Hub, Tablet, The Millions, Brevity, and elsewhere. He's currently at work on yet another travel book.

Header photo by Robin Benzrihem.