About the First Time I Met Charles Manson

Maggie Milstein took an interest in interviewing America's most notorious prisoners after encountering some men who believed that they were Charles Manson's children from the 1960s. In her forthcoming book, The Bodies, Milstein describes her many visits to the Protective Housing Unit at California State Prison, where she met Manson and several people in his orbit. In a strange twist-of-fate, she even helped organize the cult killer's secretive funeral in March 2018 (she often clarifies: "Don't worry, I'm not a fan of his!").

For Milstein, the interview process became a way to explore her own family's unmitigated grief after surviving the Holocaust, and, decades later, the untimely death of her mother from addiction. The result is a darkly humorous, completely unexpected journey into womanhood against the backdrop of male violence. In this passage, Milstein meets Manson for the first time.

Excerpted from The Bodies.

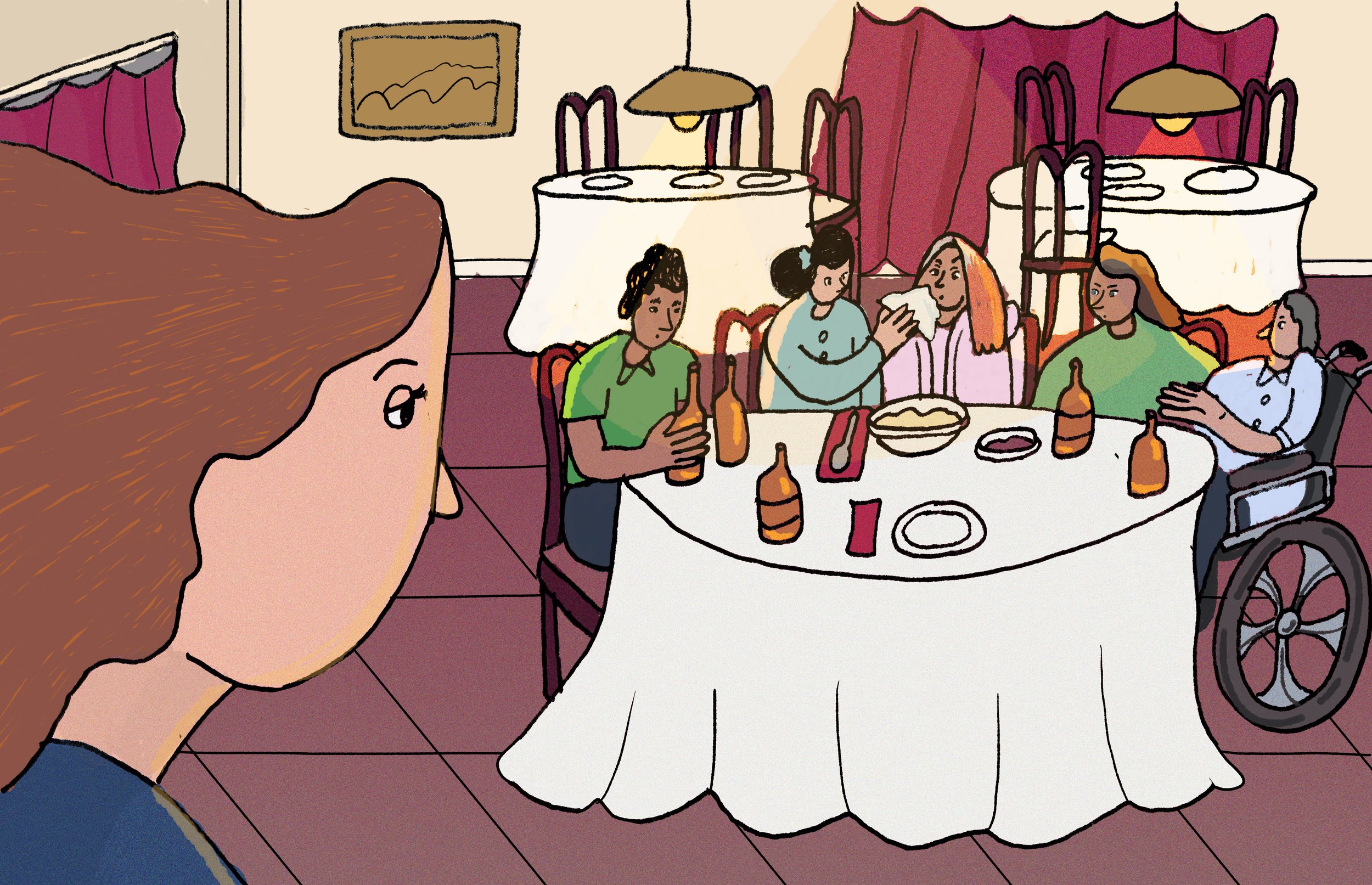

It looked like any other recreation hall—there were no plate glass windows, no phones, just circular lunch tables, a soda machine, a microwave, and a stack of board games. I instinctively looked for bingo balls. The only peculiarity was a surveillance station in the middle of the room where a group of officers gossiped and poked around on Facebook. There were two inmates: David, who sat alone at a table, and old Charlie Manson, who sat at another, talking in hushed tones with his girlfriend, "Star."

David rose sheepishly and shook my hand. He wore dark blue jeans and a light chambray shirt with a white thermal underneath. His head was shaven, but he wore his beard in a long French fork that didn't exactly counter his devilish reputation. There are rumors that David was caught up in the Aryan brotherhood, though he denied any current affiliation. Charlie had sported a similar look during the Tate-LaBianca trial, saying, "I am the Devil, and the Devil always has a bald head."

David smiled, and I noticed that the sides of his two front teeth had been chipped to form a perfect "V," a middle fang.

We talked about the weather, how he wished he could get out more. I assured him that he wasn't missing much, that the air was yellow with dung and that the prison, though unlovely, was the nicest thing in town. He apologized for his nervousness; he rarely talked to folks from the outside.

We looked at the other table, at Charlie.

I had expected to see a biblically old man, a grizzled sinner languishing outside the gates of Old Jerusalem, a defunct milk cow on a meat hook—a castaway—but found a guy more Midwestern than Levantine, whose nose had naturally widened over the years, slimming and softening his eyes by comparison. He looked almost honest. When referring to Charlie in the prime of his life, some people describe him as Christ-like in appearance: shaggy, big-eyed, and rawboned—there is a cheap irony in his past resemblance to the Son of God, one that he probably cultivated to add legitimacy to his claims of mystical power. But as he grew older, his petite frame, which had once contrasted screamingly with his megalomania, had become stocky and slow-footed, his head a weighty bust meant less for the tabloids and more for the buttered lane of a bowling alley. He still had an enviable crop of hair and beard, now gray and relatively kempt, and though his skin was doughy and shadow-less his eyes were as soft and expressive as a pig's. As he sat at a visitation table in clean blue chambray, he looked less like America's most dangerous criminal and more like the original Maytag Man, waiting fist-to-cheek.

Charles Manson with Afton Elaine Burton, or “Star,” 2014. Shutterstock.

Afton Burton, or "Star," a sliver of a girl, sat next to him, though their arms didn't touch. Loved ones are allowed nothing more than a brief kiss and hug at the beginning and end of their visits. Hand holding is tolerated in moderation.

She was twenty-five, like me. Her hair fell to her shoulders in a deep, middle part. She'd grown it past her breasts, then shaved it off for Charlie. She'd cut an "X" in her forehead, then healed for Charlie. Her hair was back, for now, and her pupils bubbled up like tar.

It seemed as though the weight of her little body kept the heavy, government-issue chair from flying around the room in the fingers of a poltergeist. She looked like Charlie's other girls, but to be fair, so did I: dark hair, baby face, yearbook grin. I resembled Leslie Van Houten, the psychopathic prom queen, while Star favored Susan Atkins, Charlie's lead girl who wrote "PIG" in blood. I didn't cultivate the look. Star told a reporter from Rolling Stone that Charlie was going to marry her and denied any connection to Atkins, saying,

"That bitch was fucking crazy. She was a crazy fucking whore."

As a teenager, Star wrote to another prisoner at Corcoran, but Charlie found her letters and wrote back. She claimed to be interested in the aging cult leader's "environmental activism" and was undaunted by his criminal past, insisting that he was innocent and that the murders were all the fault of the girls who followed him. The letters led to a visit, then another, until Star became a regular in Charlie's home. She sat not-too-close to him every Saturday and Sunday, her hair down, her tiny hand resting in his like a dagger.

David had told me she would be there. My tongue stuck to the roof of my mouth. I walked over to the Coke machine that stood between us to get a better look, my Ziplock bag of 160 quarters pulling down on my fingers like a small child. I slid four quarters into the slot and waved my finger over the buttons, which had been defaced and re-plastered with scotch tape and hand-written slips of paper. Diet Coke. The frosty can plunked to the bottom and I curtsied, easing my hand into the mouth of the machine, taking extra precaution not to bend over too far.

I glanced at Star, and made my way back to my seat, wondering what it means to be twenty-five. Perhaps it's the age when a girl realizes that her existence is finite and begins to imagine "another life," a space filled with her happy, unreasonable dreams; in another life, I will become something more. Her fantasy is a prison she can neither enter nor escape.

Eva Braun, 1937.

A photograph of Eva Braun was taken a few months after her twenty-fifth birthday. She sits on a plank in the middle of a rowboat, her eyes smiling at the camera, her long, tapered fingers wrapped around the handles of the oars. It's clear that her swimsuit was truly white, though the lake appears the color of the moon; Hitler would later give Eva a color camera under the agreement that she, and only she, could take candid shots of Der Fuhrer (he called her his chaparral, a German word meaning "a nice little girl of no importance"). By the time this photo developed, Eva had tried to kill herself. Twice. Once when she was twenty and aimed her father's pistol at her heart (she pulled the trigger and the gun jerked, unloading into the muscle of her neck), and again when she overdosed on sleeping pills the spring of her 23rd year. Historians claim that Eva made the attempts to "get Hitler's attention." In this photograph she is twenty-five, a woman kept, rowing the River Styx. She isn't allowed in boardrooms, she can't sleep in his bed. She isn't an official member of the Nazi Party, though she lives in its headquarters for the rest of her life—in a place nicknamed "The Grand Hotel." Hitler believes that, in order to capture the heart of a nation, he should appear sexually available, so Eva pretends to be his secretary. But he will bring her banned makeup and clothes and keep his pillow promise, marrying her the morning of their suicide. She doesn't see a politician in him, or Der Fuhrer, or the man who murdered my family; she sees the promise she made him: "From our first meeting I swore to follow you anywhere even unto death. I live only for your love."

Star told Rolling Stone, "People can think I'm crazy. But they don't know. This is what's right for me. This is what I was born for."

I turned my attention back to David, who leaned in and whispered, "Don't talk to Star outside of this room. You get me?"

I promised him I wouldn't.

Charles Manson in court, 1970. Getty Images.

Star sat next to the old man and brushed dirt off his shirt. He wouldn't marry her. Corcoran didn't allow conjugal visits, and besides, a wife would have cramped Charlie's style.

The front door flew open and a tall man pranced in, pushing a cart overflowing with colorful snacks. He set up camp by the surveillance station and laid out his bounty: shrink-wrapped burritos, blocks of birthday cake, pumpkin pie, personal pizzas, chips, tamales, apples, bananas, avocados, candy bars, and microwavable popcorn. David pretended not to notice and kept his eyes on Star.

"I have no idea why Star wants to be associated with that guy. Loving Charlie Manson is like having a booger hanging out of your nose."

"How elegant."

"I'm serious. I guess you can say that he and I used to be buddies. We'd pick at our guitars and play cards and shit, but he just became too much for me to handle."

"Really? Charles Manson?"

David looked at Charlie, who had risen to inspect the snacks. Charlie had been rumored to stunt in the visitors' room. I heard that, in his younger years, he jumped on tables and pretended to be an ape. He'd screech at people and throw things.

"The guy is a sad, old clown," continued David. "He puts on a show for anyone who is stupid enough to listen. He will make shit up and then deny it. We stopped being friends because he told me that he had molested children in the Family. I completely broke it off with him, even though we're neighbors. Later, he wholeheartedly denied that he had done anything. I knew that he was just trying to prove that he was badder than us."

"Do you think he did it?" I asked, the Diet Coke peaking in my throat like vomit.

"Does it matter?"

We rose from our seats and made our way over to the vendor. David hobbled over with his cane. He had sustained multiple injuries over the years and the nerves in his back popped like strings on an old guitar.

“He wouldn’t marry her. Corcoran didn’t allow conjugal visits, and besides, a wife would have cramped Charlie’s style.”

Charlie, Star, David, and I loomed awkwardly over the food and attempted conversation. In Yiddish, we call it shmoozing. Star recognized me and squeaked,

"Thanks for coming in and seeing us! Charlie, say hi to Maggie."

Charlie was soberly deliberating between a Snickers and an Almond Joy, pointing to them without touching their wrappers like a scholar reading Torah. He hobbled over and gave me a moony smile.

"Ah, Maggie! Did you have a good trip?" He held out his little, chalky hand.

I shook it, and reminded myself to wash it later. I told him that yes, I had a good trip.

"Well, I won't keep you two from lunch" I said. "I just wanted to introduce myself."

"Thanks for comin' over," trilled Star, beaming as if it were her wedding day and I had stopped by their sweetheart table.

Charlie gave me another moony smile then returned to his sugar study. Star picked him up some popcorn, an avocado, an Almond Joy, and a carne asada burrito, paying with her plastic bag of quarters. I bought David a burrito, a piece of pumpkin pie, and a microwavable pizza. I chose a piece of chocolate cake with green and red piping and frosting so thick that it had split and slid off. I didn't know if the cake had been for Christmas or Cinco de Mayo, but it didn't matter: everything and everyone had been frozen and re-thawed beyond recognition.

I waved to Charlie and Star and sat down with David, who glared at the microwave. Star had snagged the last bag of popcorn, David's favorite, and its richness filled the room.

"Goddamnit, he even got last avocado, too," sighed David in utter resignation. "He is such an ass. He and Star have built their entire empire on environmental and animal rights. They tell their fans that they are vegans and want to save the Earth. And there he is, eating a carne asada burrito."

Star pulled apart the warm tortilla with a knife and fork. Charlie sat with a napkin tucked in the collar of his shirt and stared off into space with a sweet, old smile.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maggie Milstein was an Iowa Arts Fellow and a teaching fellow at the University of Iowa's Nonfiction Writing Program. She performs interviews and research in some of America's notorious prisons in an attempt to re-invent the "true crime" genre. She lives in Los Angeles.

If you are interested in learning more about The Bodies, you can email maggieessays@gmail.com. Maggie Milstein is represented by Andrew Frances (manager) and Joel Gotler (agent). Website (maggiemilstein.com) forthcoming.

Header photo by Daniel von Appen.