About Cuba

UNWRITTEN DETAILS FROM THE OTHER SIDE OF PARADISE

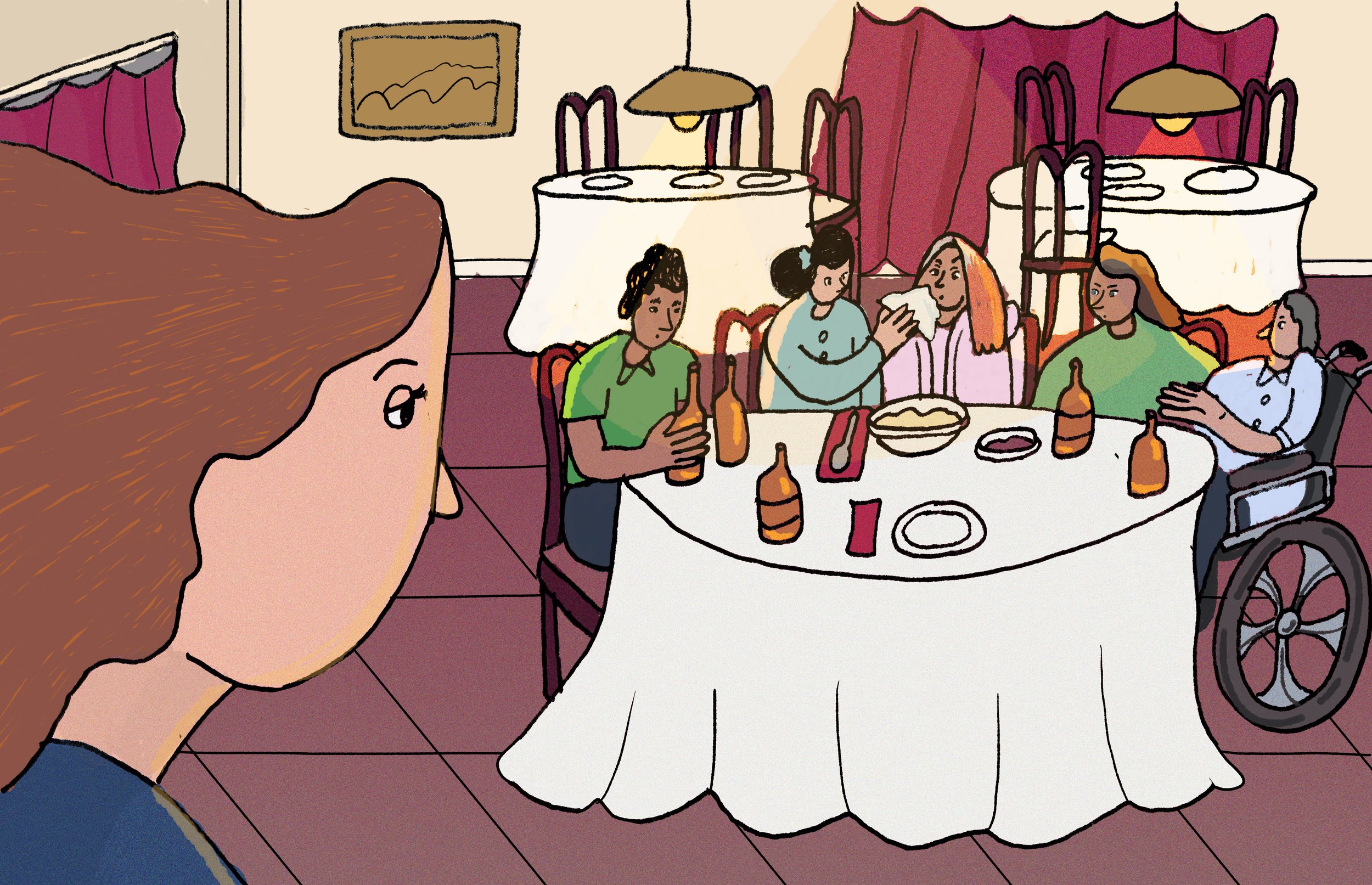

I don’t remember how we got to the Trinidad restaurant or what we had for our main course. That’s not entirely true: The plates were staple criollo food. An image of small shrimp, scent of garlic, rises in my memory. My mother and I had been on a road trip through Cuba for a week, and this was among our final stops. I’d been living in Cuba for eight months or so, and I’d fallen into the habit of not booking anything in advance. All of the best casas were full, but we found a spot anyway.

The word “restaurant” is misleading. Like I say, I don’t know who recommended that we go to this man’s house to eat, or even if he had a registered paladar, an in-home restaurant. We were alone in his back garden, my mother and I and a candle he lit on the table to combat with its tiny, glowing warmth the terrible fluorescent lighting that radiated, along with the cooking smells and clatter of pans, from the kitchen. The trees that grew up around the chipping cast-iron furniture were lush and improbable, rooted between the concrete of path and patio.

But our host had cultivated banana trees, palms, blushing flowers. He moved slowly; he anticipated what we wanted before we wanted it—bottles of water and napkins and a side of plantain fufu. He took his time with everything. He lay out two sticky plastic placemats and we ate. After dinner, he brought out a small plastic canister of Nestlé vanilla ice cream and pulled three small bananas down from a tree. He cut them into two bowls, slow, slow, in front of us.

“I’d never had anything so creamy before in my life,” my mother says now. When she tasted a Cuban banana, her eyes widened, her mouth puckered, she cocked her head and looked at the bowl, the tree, my face, back to the bowl and to the banana inside of it.

I had gotten used to them, so I had forgotten. Cuban bananas are thin-skinned, sensitive, go from underripe to pungent brown in a day, are reduced to mush a day later. But the return: a banana that tastes like banana ice cream, a banana that slides along the tongue, a banana of which my mother still says, wonderingly, “It was amazing.”

Our host that night smiled and pulled four more off the tree and set them in front of my mother. Reverently, now as slow as he, my mother peeled one, broke it into thirds, and ate each piece with her eyes closed and the fluorescent glare of the kitchen light on her eyelids.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Julia Cooke is the author of The Other Side of Paradise: Life in the New Cuba, about young people in post-Fidel Havana, and a frequent contributor to VQR, Conde Nast Traveler, and Saveur. She is the recipient of fellowships from the Norman Mailer Center, the Constance Saltonstall Foundation for the Arts, and Columbia University.