The Berliner Who Evaded Arrest

In a city with a divided past—artists, radical hackers and leftists on one side, Nazis on the other—one 70-year-old lady makes it her mission to alter hate graffiti with pink spray paint. In the process, she lights a fire of courage and kinship in the heart of an American writer.

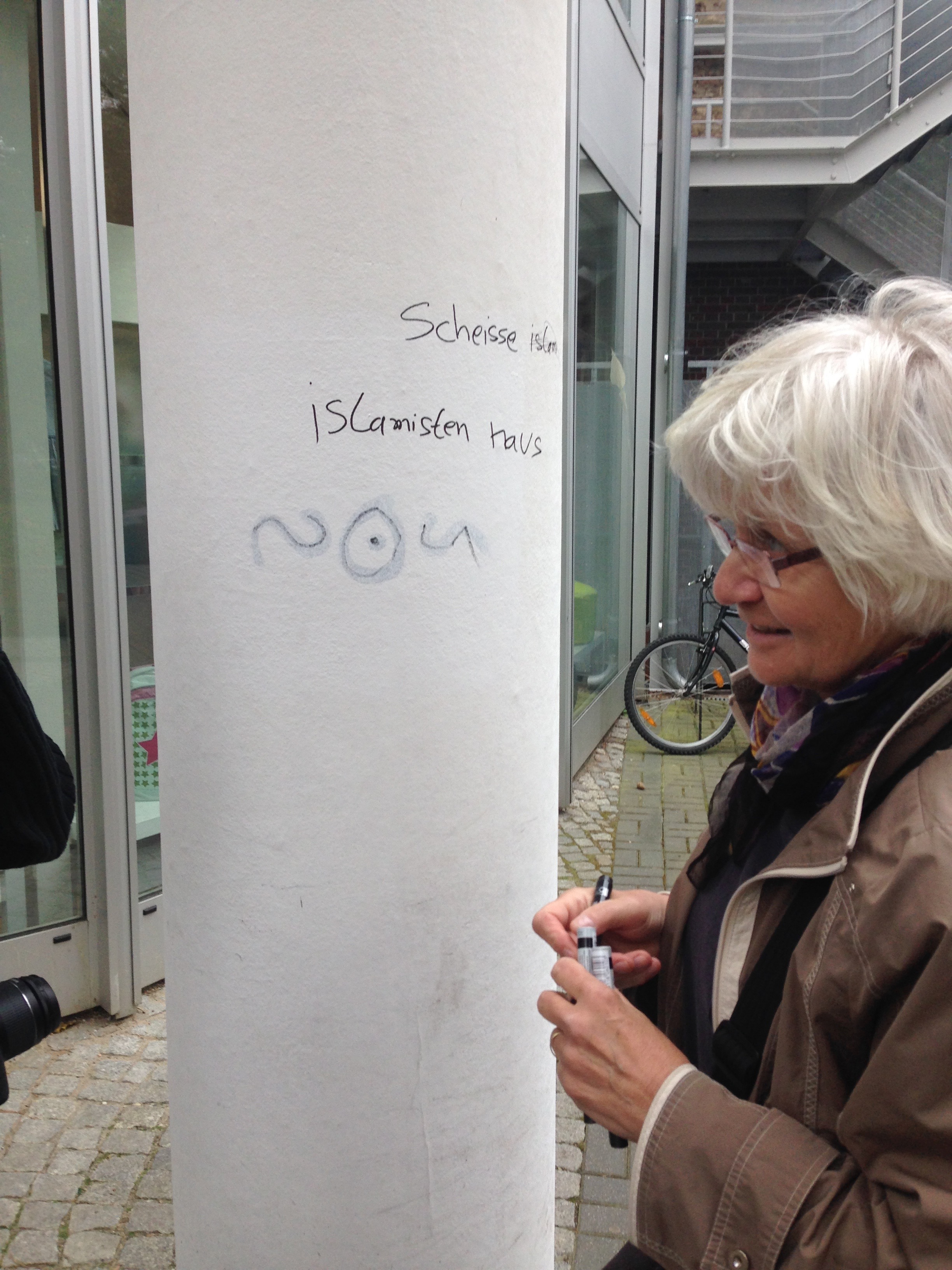

Irmela Mensah-Schramm stared at the message scrawled on the street sign. "Islamists, get out," it read.

She clambered up on a stone wall, clinging to the signpost for balance. Brandishing a permanent marker, she colored over the graffiti, changing it to say "Islamophobia, get out."

"Not bad for a seventy-year-old, eh?" she said as she leaped down.

At that moment, I viewed her with the remove of a journalist in awe of her subject. Soon, I would find myself viscerally understanding the danger my subject faced every day in the course of her mission: before the afternoon was out, Irmela and I would be standing side-by-side, together facing down the threat of arrest from the German police.

*

I had heard about Irmela the previous week at the German Historical Museum, a lace-pink artillery arsenal built by a Prussian king. Outside, statues loom on the building's flat roof; inside, stone masks stare in the colonnade parade hall. On the day I visited, the museum was showing an exhibit about the history of stickers and flyers in Germany. I wandered through the quiet special exhibit room to a back corner, where I found a binder full of neat plastic sheets ensconcing hateful stickers. Its rings strained to hold them all. A plaque explained that this binder belonged to Irmela, who had spent the past thirty years traveling around Germany removing right-wing stickers and altering graffiti in public spaces. The binders were records of all the stickers she had removed, an encyclopedia of three decades of hate speech.

Images provided by the author.

As a journalist, I have an affinity both for larger-than-life characters and for people on either particularly dastardly or particularly noble missions. Of course, recently, I hadn't been much of a journalist. I had worked full-time as a reporter in Boston during my first three years out of college, but in 2014 I had moved to Berlin to write a novel, and my created world had consumed me; my lackluster attempts to report in Germany had come to nothing. I thought I would leave the country without writing any nonfiction at all, since I was moving back to the United States in June. But when I held Irmela's binder in my hands, I was struck by the obsessive courage I sensed there. I knew immediately that hers was a story I needed to be part of.

I found her email address online and wrote to her. She invited me and my photographer husband Nate to tag along on a graffiti-removal mission in Zehlendorf, a suburban area that lies at the western edge of the former West Berlin.

“She was short and prim with admirable posture, her white hair cut in the style of the flappers who ran around Berlin back in the glittering days of the Weimar Republic. She had an impish face and carried a white canvas bag with Against Nazis handwritten on it in red.”

That day when we met her was typical of late spring in Central Europe, gray, the summer lagging behind, the air sharp with the threat of rain. Irmela was waiting for us at the S-bahn exit. She was short and prim with admirable posture, her white hair cut in the style of the flappers who ran around Berlin back in the glittering days of the Weimar Republic. She had an impish face and carried a white canvas bag with Against Nazis handwritten on it in red.

"We have a lot of work to do," she told me in German, a gleam in her eye, and led me into a brick pedestrian walkway behind the S-bahn station. She pulled out a permanent marker and bottle of nail polish remover and transformed the anti-Islam slogans scrawled on street signs in the walkway. As I watched her, although I had only known her for ten minutes, I decided she was one of the top ten coolest people I'd ever met.

“Irmela represented the best of the German people: methodically removing their shame and just as methodically cataloging it so that it will never be forgotten.”

Irmela had started removing hate graffiti one day in 1986, when she was on her way to her job as a social worker in affluent, upscale Zehlendorf and saw a sticker on a bus stop calling for freedom for Rudolf Hesse, a Nazi war criminal. The sticker bothered her all day, and on her way home that night, she stopped and scraped it off with her key. Relief flooded her; she kept doing it. As of that day in 2016, she had removed or altered more than 70,000 stickers or pieces of graffiti.

Lately, Irmela had seen more anti-Islamic and anti-refugee slogans and stickers. At first, many Germans had welcomed the million refugees admitted to their country in 2015, especially in Berlin, a city of artists and radical hackers and leftists. The previous fall, my artistic, professional friends had all spoken with enthusiasm about helping the new arrivals. By May 2016, I still knew many people who were volunteering at refugee dinners or teaching English lessons. But in others, ugly resentment had started to fester. There were the panicked news articles after the alleged attacks by immigrants in Cologne on New Year's Eve. There was the Austrian I met who dismissed refugees as apes. My friends who cautioned me against visiting the Turkish area Kottbusser Tor, where I liked to eat donor kebabs and browse the market, by saying, "People will try to sell you knives if you go there." The pleading sign I saw hanging outside the Dresden Art Museum: "Citizens! Don't allow the spiritual and intellectual climate in our country once again to move towards right-wing ideology!"

Berlin had been bohemian before, in the 1920s, when it bred communists and writers, flappers and queer sex clubs. Christopher Isherwood, the British writer, chronicled those years in his Berlin Stories, which gained immortality in the musical Cabaret. Just like me, Isherwood moved to Berlin to write because of the city's reputation. Life was a cabaret, a seedy but inclusive and artistic space where it was possible to ignore horrors—until 1933, the year Isherwood left Berlin, the year the cabaret shut down.

In the walkway that day, some passerby glared at Irmela, muttering under their breaths. After an evil glare from one man, she cast a chummy eyeroll at me. I rolled my eyes back, hard. I didn't think 1933 would unfold again, in Germany, anyway, but still, even a drop of that poison was too much. I hated what I saw in my temporary homeland, and I felt myself edging closer to Irmela. I'm on your side.

I had only scheduled an hour to interview Irmela, but when she told me that she'd heard about some right-wing graffiti on a wall on the other side of Zehlendorf, I followed her, without hesitation, onto a bus.

To me, Irmela represented the best of the German people: methodically removing their shame and just as methodically cataloging it so that it will never be forgotten. On the bus, she pulled out a stack of 4x6 photographs and showed me pictures of swastikas and stickers raging against asylum seekers, pro-Hitler symbols and anti-Muslim screeds.

We passed the yellow bricks and red roof of Zehlendorf Town Hall, and in her calm, melodic northern German accent, Irmela explained that she had first exhibited her stickers there in 1995. Since then, she had received medals and commendations from the German government. She had exhibited in Italy and Finland, and had run workshops to teach children to follow in her footsteps. Sometimes she passed out photocopies of graffiti that said "foreigners to the gas chamber" and told her students to change it to "foreigners to the fun chamber" ("gas" and "fun" rhyme in German).

“In the distance, I could see a now-defunct checkpoint that had separated West Berlin from East Germany. It was as innocuous as a tollbooth, but it was a reminder of the evil history of violence and division here.”

I flipped to the questions I'd scrawled on in my notebook. Was she ever frightened, during her expeditions? Oh, yes: she had her enemies in Germany. Once, in the small East German city of Kottbus, she was wiping away a Hakenkreuz, a swastika, on a dead-end street, alone.

"Then a Nazi came along, with long hair—they have long hair these days too—and he said, 'What are you doing there?'"

She told him she was removing an illegal symbol—the swastika is illegal in Germany. She and the neo-Nazi stared at each other, and then he turned around and ran off.

"I give you my word that it happened like this," she said, her eyes gleaming. I imagined keeping my cool, staring down a Nazi.

The police also bothered her sometimes, likely called by a combination of right-wingers and by ordinary Germans who abhorred the sight of someone breaking the rules. But she had never received a fine or any official punishment. Sometimes, the police even praised her.

"Once, a woman called the police and said I had 'smeared graffiti,' in a train station," Irmela explained. "The police came and said to the woman, 'We must disappoint you.' She said, 'Why?' The police said, 'Because Frau Schramm did well.' The woman made such a face!"

In her collection of photos, one appeared showing two cats curled together. "Oh, those are my cats," she chuckled. "They're not Nazis."

Our interview ended with the voluminous sound of brakes. I followed her off the bus onto a highway that swept away from Berlin through red cedar pine and birch forests, with gray Ostblok-era apartment buildings rising to our right off an access road. In the distance, I could see a now-defunct checkpoint that had separated West Berlin from East Germany. It was as innocuous as a tollbooth, but it was a reminder of the evil history of violence and division here, in the years after the cabaret shut down.

I trailed Irmela along the access road, prickly with excitement about my continued role in her mission. I wasn't frightened, even though we were going to commit a crime. Long ago, I had discovered that if a story was important enough to me, I could slip into a cognitive dissonance that allowed me to forget about my own physical safety while in the role of journalist.

There, along a waist-high concrete wall, screamed a right-wing slogan: Merkel Muß Weg, or Merkel must go. Irmela pulled out a pink spray can from her bag and got to work changing the message to Merke! Hass Weg! (Remember! Hate away!) As I scribbled in my notebook, I noticed that a car had pulled off the highway above us. A woman was standing in the breakdown lane, screaming down at Irmela. I couldn't hear her in the rush of traffic, but I saw her face, twisted into righteous rage. I saw her taking pictures.

Then a man emerged from the park behind the apartment building off the access road. He was middle-aged, a hard silvery man in a black leather jacket. A type around these hinterland districts of Berlin.

The sneering man asked Irmela what she was doing. She told him, disdain dripping from her voice. She didn't even look away from the fuchsia exclamation point she was emblazoning on the wall.

“I didn’t question whether it was wise to remain in the area. We had stumbled on right-wing graffiti. Who would remove it, if not us?”

He turned to me. "Why are you taking notes?"

I didn't break eye contact. I would not let him intimidate me, I decided. "Ich bin Journalistin."

"Oh really? Where's your press card?"

Who has a press card anymore? I had never even had one when I'd worked for the newspaper in Boston. I told him so, trying to match Irmela's tone.

He threatened to call the police. She said, "Go ahead. They know who I am."

The man stalked off. Irmela finished the slogan, snapped a picture, then said, "Come on." She didn't seem nervous, but still, we hurried away into a narrow, low-ceiling tunnel cutting under the highway.

There, another Merkel Must Go glared at us from a concrete wall.

Irmela stopped, rummaged in her bag. I stopped too. I didn't question whether it was wise to remain in the area. We had stumbled on right-wing graffiti. Who would remove it, if not us? Out came the spray can and Irmela started to change the slogan.

That's when the man on the bicycle showed up.

Nate told me later that he was afraid that this muscular man with his unmarked black windbreaker and shaved head was a neo-Nazi. But I didn't even think of it; I was deep both in Irmela's mission and in the notes I was scribbling in my well-worn reporter's notebook. Then, the man showed us his badge. He was a plainclothes officer with the Berlin police, and he demanded to know why we had vandalized the tunnel. "It's very expensive to clean this off," he said.

The twinkling woman from the bus disappeared, and a new Irmela screamed at him, her voice hoarse, "Then where were you when it just said 'Merkel must go'?" I saw, then, the woman who had spent years scaring or manipulating neo-Nazis and police, who was angry, perhaps, or perhaps had learned to exaggerate her rage to catch them off-guard.

The officer demanded our identification cards. Nate and I meekly handed ours over; Irmela whipped hers out and threw it on the ground at the officer's feet. "Oh, that's very nice," he muttered as he picked it up.

He escorted us from the tunnel and radioed for backup. Nate sent a text to four of our friends: "We are about to get arrested. Call us in an hour to make sure we're okay." I hadn't even thought of making such contingency plans; I, who had never been in trouble before in my life, watched these events unfold with a calm at odds with my usual high-strung nature. Meanwhile, Irmela's arms were crossed, her contempt for the cop written in every angle of her body.

I pulled him aside and asked him why Irmela's actions were illegal. He explained that removing Nazi messages was one matter. But there was nothing illegal about Merkel Must Go, and it angered him personally that she was costing the taxpayer money by defacing public property. I don't know if this officer secretly sympathized with the right-wingers who had put up the slogan, or if he simply believed in the rule of law. There are many reasons why ordinary people uphold or defend dangerous ideologies; I think many Americans have known this for a long time, and more realize it every day.

Meanwhile, Irmela was rolling her eyes like a teen who'd been caught red-handed. Then the backup arrived: two concerned young officers in a patrol car. After a frenzied conversation, the original officer left, and the two new officers got to work figuring out what to do with us. They were about to descend into the tunnel to take pictures for evidence when Irmela whipped out her camera. "You don't have to take pictures," she said. "I already did." She showed them the slogan she had altered that day, as well as all the work she'd done that week. "What about this?" she said, pointing at a swastika. "Should I have removed this? How about this one?"

Irmela's personality had changed again, and I realized that over the thirty years of her mission, she had become an expert on human psychology. She had transformed into a firm but endearing Oma for these young men. After ten minutes of her showing them pictures and asking, "Come on, you agree with me, don't you?" one of them said, "All right, I, personally, agree with you. I just have to do my job."

They decided that Irmela would receive a fine, and that they would let us go. But first, they needed to confiscate the spray can. "No." Irmela jerked her bag away. "I don't have it."

"Come on," said one of them.

Glowering, Irmela pulled one spray can from the bag and handed it over, and the officers drove off.

"Hey, look what I have," Irmela turned to me and Nate, pulling out two more spray cans. Her face lit up as she showed us how she'd tricked the officers. I felt like jumping up and down like a little girl. Hopped up on danger and conspiracy, we hurried to the bus stop together like old friends.

When I said goodbye to Irmela on the bus, she clasped my hands tight between hers. On the S-Bahn ride home, I was giddy. I felt that Irmela and I had truly been through something together. The hand clasp had cemented our shared afternoon of fighting the madness seeping into the country. I had walked in her shoes, struggled at her side, become part of her story. We had built a kinship between us.

“This, I think, is the great delusion that journalists and writers must allow ourselves: we must believe that we can try on the lives of others, that we can recreate their struggles and triumphs on the page, when by necessity of our profession, we are always transitory.”

A week later, I moved back to the United States. That summer, in a dorm room in California at a writers' workshop, I wrote a brief piece about Irmela and her mission for the Financial Times' glossy weekend magazine. Then, Irmela emailed to tell me something shocking: the police had mailed her a summons. For the first time, she was being punished. I don't know if her luck finally ran out, or if they had cracked down on her because of the tensions in Germany. Either way, her case went to trial and in October 2016, the Berlin Supreme Court handed down a suspended 1,800 euro fine, which she would have to pay if she were caught again in the next year. Of course, she appealed the decision, and she assured me that her work continued: she had recently removed an 88, which is a neo-Nazi symbol for Hitler, as well as a fuck asylum seekers sticker.

She started appearing everywhere in the English-speaking press. As I read these stories, especially the ones that mentioned her near-arrest and fine, I felt a strange sense of propriety. I was there, I thought. None of these stories are sharing the tense details of the first time the German government turned against her, because none of those other reporters were there. I remembered our shared glee over the hidden spray cans, her clasping my hands on the bus.

But, then, the truth of it: I had no propriety over Irmela's story, and our shared struggle was an illusion. This, I think, is the great delusion that journalists and writers must allow ourselves: we must believe that we can try on the lives of others, that we can recreate their struggles and triumphs on the page, when by necessity of our profession, we are always transitory. I had wanted to be part of Irmela's story, and I achieved this, but only for an afternoon, one of my last in Germany. We had clasped hands, but then, just like Isherwood before me, I moved back to the United States, and I never saw her again. I never even received my fine in the mail.

Still, though, I thought of Irmela when swastikas appeared in my home city in the stunned days after the 2016 election. I've thought of her often in the past two years. Of what madness she might choose to combat if she lived in America. Of her tenacity, her bravery. Of her conviction that the words and symbols we surround ourselves with matter, and that it is possible to change them, marker-stroke by marker-stroke.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emily Cataneo is a freelance journalist and fiction writer. She started her career as a full-time reporter writing about local issues in Boston, Massachusetts for papers including the Boston Globe. As a freelancer, she has reported stories in Germany, South Korea, the United Kingdom, Iceland, and Mexico, for venues such as the Financial Times, Roads & Kingdoms, Atlas Obscura, and NPR. She likes history, hats, craft projects, and dogs.

Header photo by Lobo Studio Hamburg.