3 p.m. in Requena

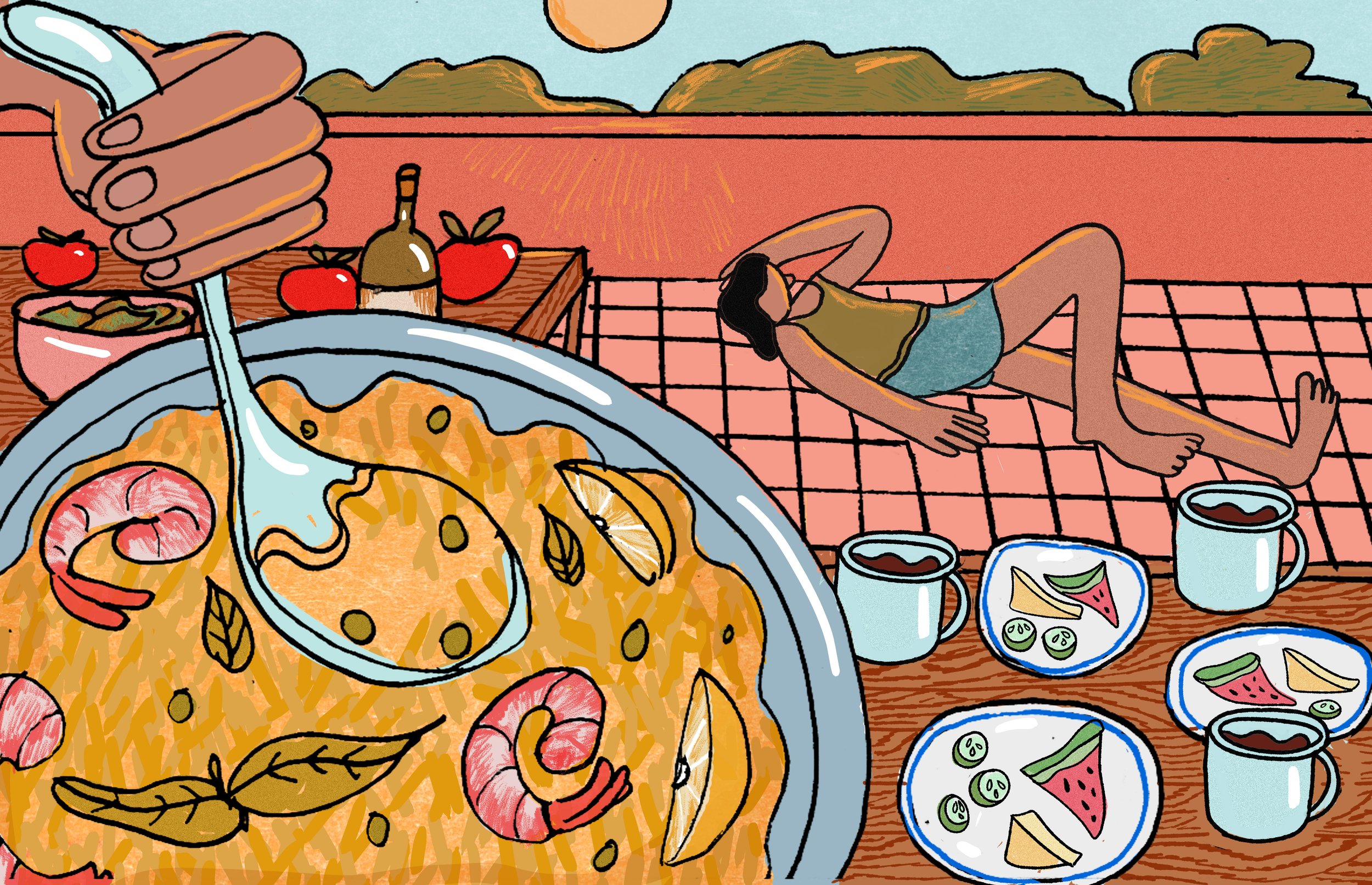

3 p.m. in Requena is time to eat. Yes, you ate breakfast on the terrace four hours ago: peach wedges, watermelon triangles, crisp wafers of cucumber. Slick, salty discs of queso fresco and tongues of jamón cut straight from the leg, brown and glistening with ribbons of fat. A metal carafe that poured rich green-gold olive oil over toasts shaped like tombstones. Tomatoes dusted with salt like the winter roads in the town you were born in, 6,000 kilometers away, where food was less enjoyed than endured, Lean Cuisines bought in bulk and eaten alone standing up at the kitchen counter.

But now you’re in Requena, a small town in eastern Spain’s wine country. You took a train here yesterday, an hour and a half from where you live in València. When Inés, who grew up in Requena, invited you to visit with her for the weekend, you’d never given a faster “yes.” Inés is the first Spanish friend you ever made and precious to you. You met her a year ago, at a guiri’s goodbye party. The two of you clinked watered-down vermouths and charmed each other, then fed your burgeoning friendship by seeing a steady stream of films in their original languages—you’ve racked up Catalan, Galician, Spanish, Italian, French, Korean, and English—and discussing them over cold beers and salty peanuts.

After arriving in Requena yesterday, you went wine tasting with Inés’s friends from home, trailing up and down dusty rows of vines that reached your waist. You drank pale yellow wine and kept track of your glass easily because it was stained with berry lipstick. You didn’t drink enough to be hungover—you haven’t done that in a while—but you didn’t sleep great in the blue sheets of Inés’s childhood bedroom, so breakfast was a salve.

In this country where no one works in August, digestion is an honest day’s labor. Desayuno, almuerzo, comida, merienda—four meals before you even conceive of dinner. Each occasion with its own alcohol: coffee floating on rum, frosty glasses of beer, bobal as purple-red as a bruise, small shots of sweet mistela. Now it’s 3 p.m. and Inés is declaring the paella is ready, so it’s time to eat again.

For the brief period between your first meal and your second, you lay digesting on the smooth tiles of the patio that stay cool even as the summer sun climbs. The water in the pool to your right looks like a sheet being shaken as wind rakes across it. An open 50-liter bag of garden soil (origen España) is lolling against the garden shed.

While you watch the shadows fall across the heavy brown shades that bracket the house’s windows, Inés and her boyfriend Adrián prepare the paella. You ask if you can help and they won’t let you. They lug the metal burner, its three rings coated in rust, out of the shed and onto the outdoor grill. They connect its gas hose—black and kinked like a diver’s breathing tube—to the butane. No one cooks paella over wood fires anymore, they tell you, not since Franco.

Inés cuts up chicken and rabbit and drops it in shiny olive oil. She adds garlic, which sizzles and pops, then scrapes rough-chopped kidney beans off her cutting board and into the center of the pan. She pours in pureed tomatoes and nudges them around with a perforated spoon before adding rice and water. Steam rises past the bricks turned black from past paellas. She dashes salt over the mixture and lays sprigs of rosemary across it like an offering.

Watching her, you feel warm not from the sun but from the way Inés is caring for you.

Your mom, before she got sick, was a great cook. She believed in long, involved processes that led to rich, indulgent meals. The day before she made her red sauce, she’d roast a whole chicken, using the meat for chicken salad sandwiches on toasted white bread, and the bones for homemade stock. You can’t not think of her, lying next to turquoise water and underneath azure sky, being cooked for by someone who loves you and is good at it.

Now the paella, a burnished shade of saffron gold, is ready. Inés and her brother, whose name you’ve forgotten though it was told to you twice, each grab a handle and swing the pan onto the middle of the patio’s table, where it’s shaded by a roof of terracotta tiles. Inés gives everyone a spoon and instructs you to eat directly from the pan. You do. So does Adrián. So does Inés. So does the brother.

On this 96-degree Sunday afternoon in Requena, you feel your wet bathing suit dampening the front of your t-shirt and sweat pooling under your arms, but you’re still comfortable. You savor sitting here in a black plastic chair at the table of this blonde-haired valenciana, doing what we do when fed and cared for by someone: sitting and sipping and sweating and scooping another serving of rice.

If you listen hard, you can hear cars passing on the highway. Families that have already finished their comida and are heading back to Valencia. Later, Adrián will drive you there, too, the city you hope to be buried in, ready to stay still after years of moving across continents. For now, you reach forward, scrape off a spoonful of socarrat—the extra-crispy almost-burnt rice from the outer edge of the paella—and let the succor melt onto your tongue.

About the Author

Katherine Plumhoff is from the Great Lakes and now lives near the sea. Her writing has been nominated for Best Small Fictions and supported by the Foundation House Artists’ Residency. You can find her fiction in Flash Frog, Gone Lawn, and Heavy Feather Lit Review, her nonfiction in Litro Magazine, and her books in uneven stacks.

Illustration by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure.