7 a.m. in Kelso

7 a.m. in Kelso is the smell of disinfectant and hay. It's bacon and egg sandwiches from tiny food trucks. It’s the animal heat rising soft from pens inside huge canvas tents. The tups paw a metallic rhythm against their empty troughs and snout in the straw. Their bodies pulse with short panting breaths, a sign of their worry. Around four thousand of these young rams will be auctioned here today, an event which draws in Scottish farmers, buyers from around the U.K. and abroad—and me.

I’m here on an artist residency, writing about the connection between human and animal, the way our bodies are intertwined through husbandry. It is mid-September, harvest season in the Scottish Borders, and everywhere around me hums with labour. In the evenings, tractor beams flood the fields, catch flickers of eyeshine and russet as the hares dart back into the safety of darkness. In the mornings, I am met with tightly wound bales, sculptural in their architecture. When I walk through the small paddock to get to my writing room, I scatter the geese and ducks that are kept here by the gardener, an amateur fancier. He tells me affectionately that he is going to try to breed his Toulouse, and we watch as the couple carry their heft away from us, their low-hanging stomachs brushing the floor with each step.

Here in the Scottish Borders and elsewhere, tups are sold for the production of offspring. Their only purpose is to be fertile. Today’s sale is the culmination of sixteen months of rearing, and there’s an undercurrent of anxiety between the farmers as to whether these rams will be worth the cost of keeping them alive. Some of the pens are decorated with rosettes, complex scales charting fat and body mass, the average survival rate of the lambs they should help to produce. What is our relation to the animal when we see in them a second body, one not yet realised? I want to tell them that I understand what it is to be examined. My own fertility is in question, too. And although the tups are male, the whole place hums with a heady fecundity that reminds me of my own lack of a small and mewling infant. Occasionally, a tup rests its head upon another’s back, or pokes a nose through the fence that separates him from his neighbours for a tentative meeting of cheeks. And I have to pin my arms tightly to my sides to quell the desire to reach out and scratch a nose or behind a long ear, even when one sticks his head out between the metal slats and flashes me his coarse teeth and pale pink tongue, thinking I have feed in my hand.

The crowds thicken as the buyers begin to arrive, looking through the catalogue listings, taking notes. There are many different types of ram, and each is distinct. Apart from the short nose and cloudy-puff of the Suffolk, there are no others I recognise. Vendéen. Berrichon. The Texel has a piggish face with bulging eyes and a flat skull. It is less rotund than rectangular. They snuffle and scrape. Some cough. Lleyn. Charollais. The Bluefaced Leicester’s stately and regal, with a sloping Roman nose that starts high on the brow. Many are shorn with a smart V down their necks to elongate them.

The term husbandry is entwined with the role of caregiver, and there is something domestic in the tender beautification happening here. Leg hair brushed into silky fineness, hay swept off backs. A cloth is sprayed with a mix of soap and water and a tup's face is held in place by two pairs of hands while it is wiped down like a messy toddler. Others have been dyed a sort of radioactive deep yellow to make them look bigger than they are.

I watch a teenager climb over the fence and into a pen to check a Suffolk. He spreads his hands wide across the tup’s back to ensure there’s some heft to it, that the coat's styling doesn’t disguise a scrawniness beneath. He opens the mouth to inspect the teeth. In order to make sure he can chew the grass, the teenager’s brother tells me, to make sure it doesn’t just slip down. Problems with feeding means potential problems with the lambs, too. And when the margins are so narrow, the body of this animal needs to function perfectly. At this age, the tups can weigh close to a hundred kilos. To catch the tup, the teenager has to pin it into a corner, using his legs as a kind of fence.

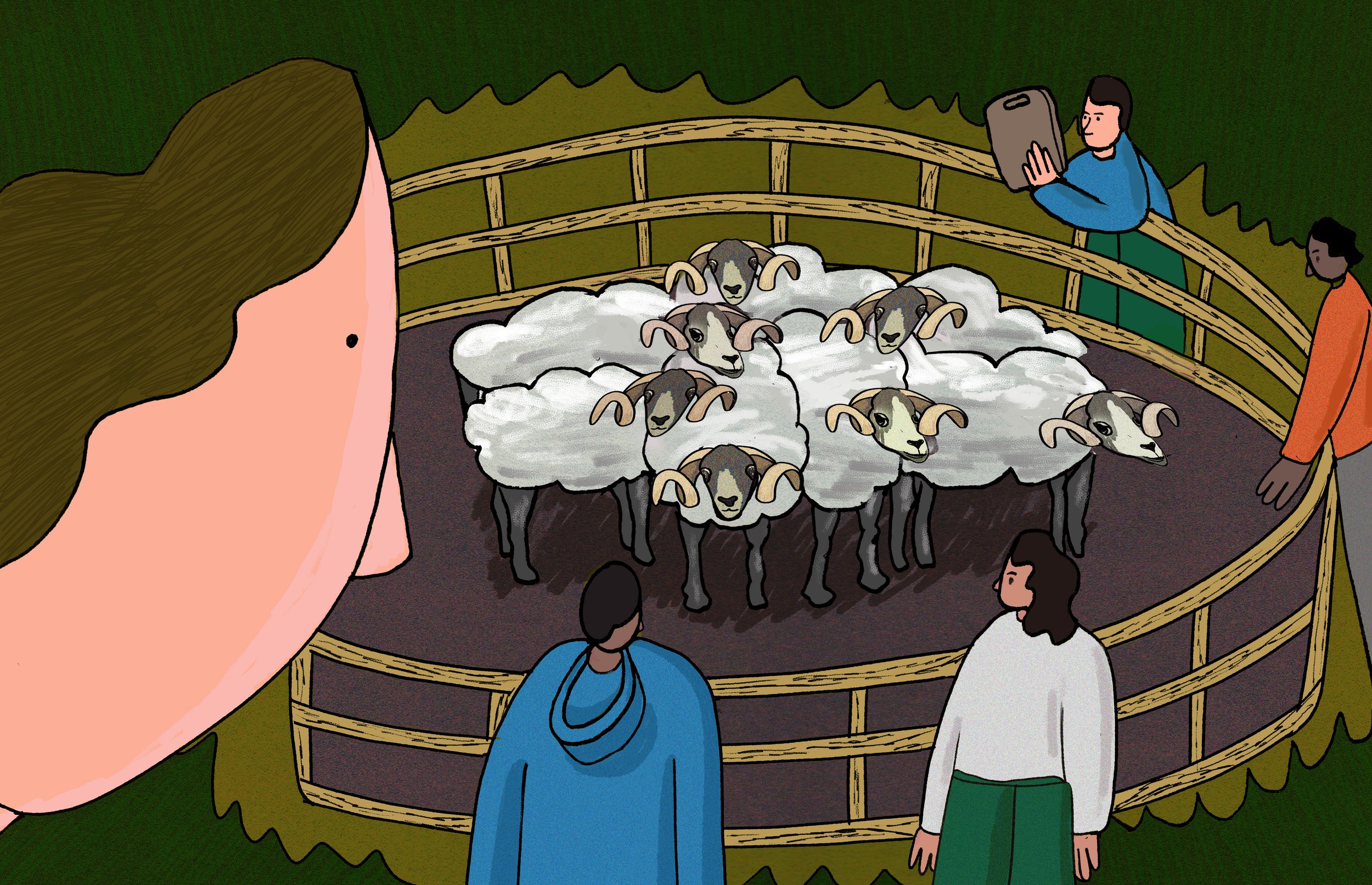

Whenever anyone enters the pen, they all cluster together, dropping their heads in one direction, trying to act inconspicuous in an attempt to become one soft mass. Whether they will fulfil what is expected of them will only become apparent in the spring, with the marking and swelling of each ewe, and the arrival of the lambs, slick wet and unsteady on their feet.

About the Author

Emma Jones (ekj.ink) is an art writer and essayist. Recent writings can be found in Source magazine, Gutter Mag and Photomonitor. In 2024 she was longlisted for the Anthony Burgess/Observer prize for art writing, and was a writer in residence with the Jan Michalski Foundation. Emma is from the UK but lives in a van, so she travels around a lot.

Illustration by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure