Dusk in the Rubʿ al Khali

Dusk in the Rubʿ al Khali is stepping outside into air that feels the same as your body, like when you get used to pool water and forget you are wet. It’s not about the temperature but a subtler, more diffuse kind of equilibrium. The desert sand doesn’t sparkle or shine; this sand is matte, suede, and there is a warm soft fleshiness to it, something that lets you know it’s healthy. Skin is the largest organ, and the Rubʿ al Khali is an expanse of skin that’s been draped over the earth, a thing that cannot exist without the goings-on of an alive body pumping away just under the surface. Some say the first djinns were desert spirits here; maybe it’s their heartbeats that sustain it. Some say there is a great city deep under the dunes, the Atlantis of the Sands. I don’t all-the-way believe in djinns, but I have no doubt a great city could rise and fall to be swallowed in a sighing wilderness like this.

The Bedouin named it the Rubʿ al Khali, “the Empty Quarter.” I have known many deserts and this one feels both empty and full: You won’t find a larger expanse of uninterrupted dunes anywhere, not even the Sahara. A place like this is called an “erg,” but I prefer the other English name: sand sea. I didn’t know the terms “erg” and “sand sea” before I moved to Abu Dhabi, a city between the Empty Quarter and the gulf, where the air felt like a warm, settling fog.

I used to pile friends, acquaintances, anyone who agreed into a white 4WD and drive south from Abu Dhabi on a long straight road, then off of it. No matter where I live, I am often making my way into deserts—the driest, barest, most scorching places, where any lingering bone-deep winter chill rises, mist-like, and sizzles into the air. In the Abu Dhabi desert especially, the heat drove my anxieties to the surface and sluiced them away with sweat. My brow would unfurrow, my shoulders drop. Muscles can’t stay scrunched up in a heat like that—they get wrung and then unwound, so that in the desert the outlines of my body are not so sharp.

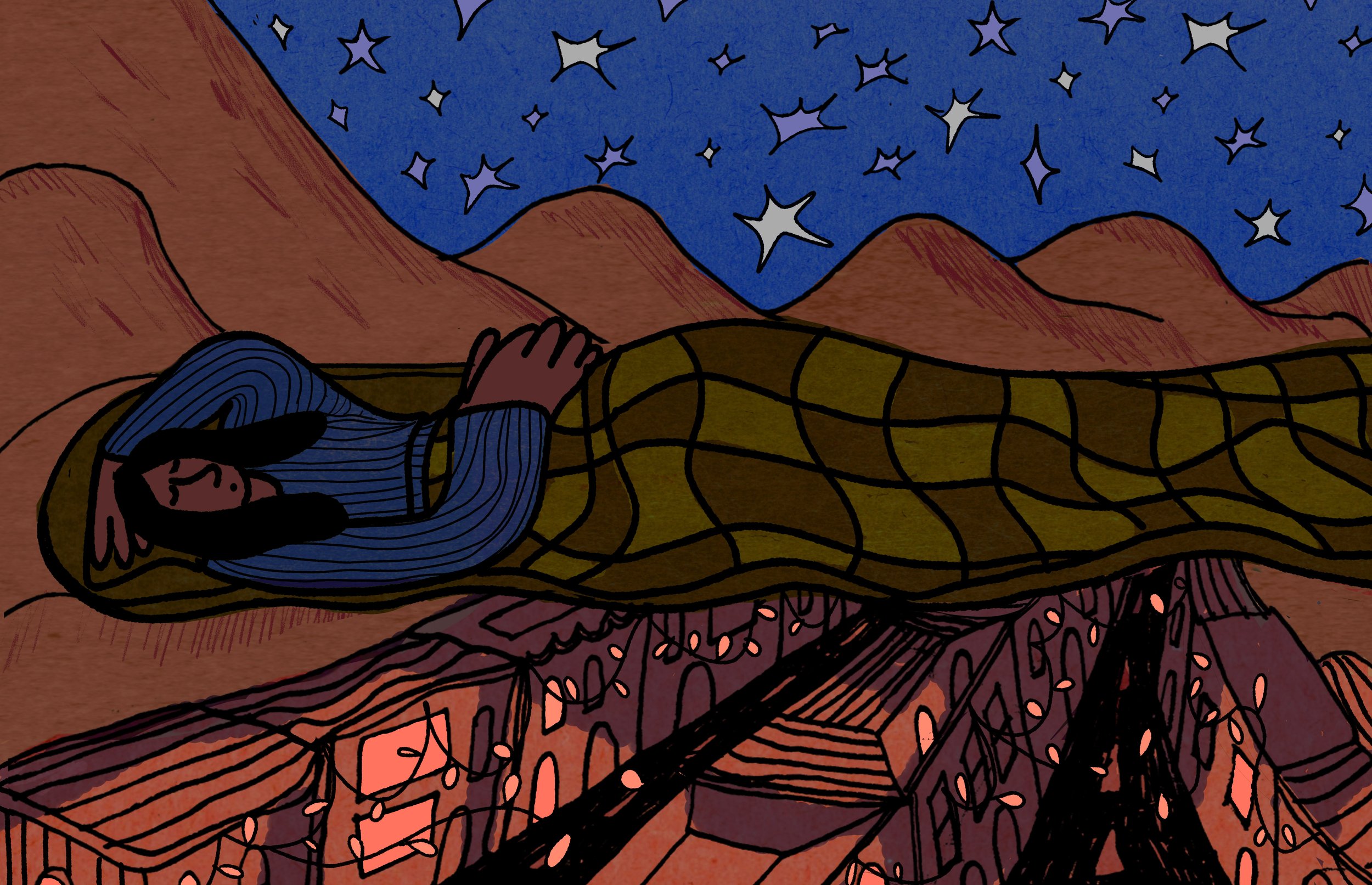

In the Rubʿ al Khali, I loved to put my sleeping bag down at the base of a dune and sit in the mellowing evening light, watching the rippling expanse of desert come to rest. Sometimes I would see a scorpion or a little desert rat, but there was never a hiss or any noise as they disrupted the sand; it seemed to absorb their sounds. After sunset, when voices grew quiet, you could hear the faint, rushing sigh of blood, not unlike when you hold a seashell to your ear. Whether it was my own blood swirling in my skull or whether I was overhearing something outside myself, I can’t be sure.

During my last trip to the desert, a few months before I left Abu Dhabi, I was lying down and looking up blearily at the miasma of stars clouding the black sky above me, having tried and failed to divine where I should go next. The earth was warm under me. Before long I heard in my head an old meditation tape my mom used to play when I would fret in the night: Imagine your limbs one by one, and feel each part of your body sinking into the bed below you. And sure enough, the sleeping bag dissolved as I sank into my warm bed, the cells of my skin rearranging and getting to know the skin-cells of the desert, and slowly the Rubʿ al Khali made its way over and through me, and it inhaled me like an ancient city, then sighed.

About the Author

Hannah Walhout is a writer and editor whose essays and food writing have appeared in Catapult, CityLab, Eater, Electric Literature, Food & Wine, Travel + Leisure, and more print and digital outlets. She also holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from The New School. She has lived in Seattle; the Inland Empire; Rome; Abu Dhabi; and now, the greatest city in the world (Brooklyn).

Illustration by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Tusshara Nalakumar Srilatha.