To My 11-Year-Old Father in the Camp

This essay was part of a collaboration between OA and the VONA Travel Writers of Color Workshop.

When our buses first pull up for the memorial service, all I feel is the heat. It is dry as an oven. I want to take photos of people, but it feels intrusive. So I point my camera upwards to the cirrus clouds littering the sky. I look around for the landmarks you described in your manuscript, those typewritten pages recording your wartime imprisonment: Castle Rock and Abalone Mountain towering over this drained lakebed valley. I want to see what you saw, walk where you walked. The sagebrush blowing around doesn’t even seem hydrated enough to root to the ground. It’s a hostile landscape.

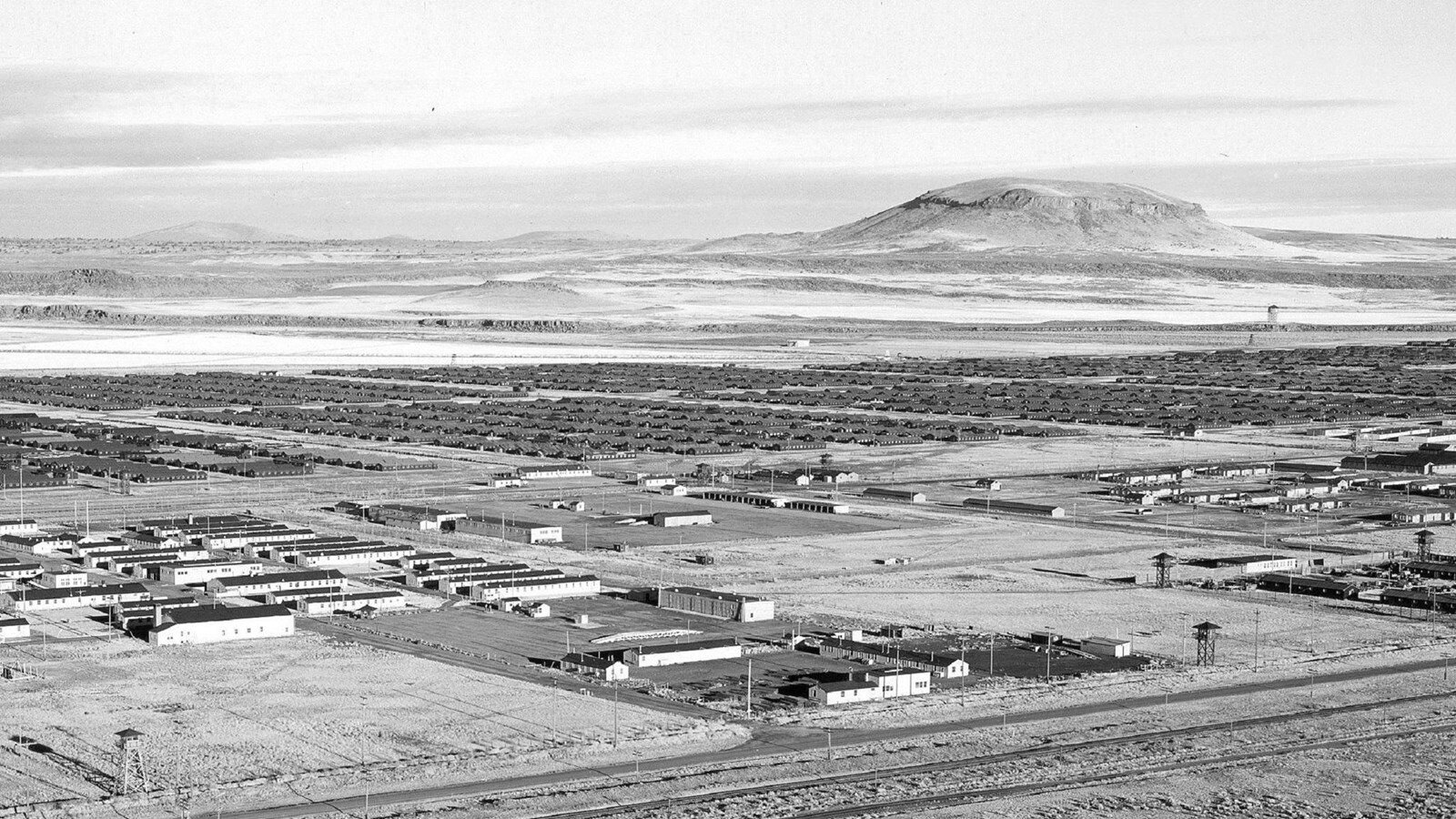

The organizers of this pilgrimage to Tule Lake, this former concentration camp in Northern California, have done their best to create a physical gathering space using the coordinates of the original camp cemetery. A white tent set up for elders, with folding chairs. Essential, in this heat. A long table with a diorama: black replicas of barracks and white tea lights in front of signs naming the ten major concentration camps where Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II. Park rangers are helpfully passing out bottles of water. Reminding us, please, stay hydrated.

From age 11 to age 14, you lived here: Family #25401, your parents with their six children, Block 45, Barracks A and B. For decades, I have pictured you waiting in line for the mess hall and the latrines, counting the number of guard towers, shivering under scratchy Army blankets at night. A young boy far removed from the you I knew: the father who would joyfully belt out “Food, glorious food!” before Saturday morning breakfasts, the teacher who taught me how to spell “chrysanthemum” with bright magnetic letters before I went to kindergarten, the librarian who paraded me and my toddler sister through several floors of offices, showing us off to your co-workers. Though I have your written memories of camp, this memorial service is my first physical encounter with Tule Lake: a name I’ve lived with for so long. A chance to meet the child I never met, the child you once were.

*

Here is a meager inventory of what’s left at the Tule Lake site: a concrete foundation of a communal latrine, the holes less than six feet apart. A building for the white officers, built by Japanese Americans. A jail built by inmates for other inmates. And yes, a weathered memorial plaque on a lonely road that concludes, “May the injustices and humiliation suffered here never recur.” A guard tower and a barrack have been transported miles away to the museum at the local fairgrounds. No barracks remain onsite, so I can’t find where you lived or walk the same paths you did. I can’t help feeling what’s here and not here.

We are on the second day of this biennial pilgrimage. Several hundred pilgrims—Japanese American camp survivors, descendants, and allies—have arrived from all over the country. When Auntie Sadako, your younger sister, invited me to come to this year’s pilgrimage, I had just reopened the manila envelope containing your typewritten pages, rereading what I hadn’t seen since I was a child. I’d just left academia after twelve years, grieving a tenure denial as painful as a divorce. I wondered what you would have said to me, to comfort me in the wake of what felt like a colossal professional failure. I thought: maybe I can write a book. And, if I’m writing a book about you, I should at least see the place you describe in your own recollections.

From 1942 to 1946, thousands of Japanese Americans were imprisoned here, reaching a peak population of almost nineteen thousand inmates in 1944, living under conditions so unhealthy that my uncle Hiroshi, your brother-in-law, describes Tule Lake as a mental institution in his own camp memoirs. Only after the pilgrimage do I learn about the circumstances of some of the Tule Lake deaths. An Issei bachelor who committed suicide. A young truck driver, killed in a preventable work accident. Babies who many believe died from poor care because they were born into a camp hospital with a racist white head physician. I allow myself to start to feel more: the confinement, the displacement. Only later do I wonder if these are reverberations from you, from the collective prisoners, maybe even from the Modoc tribe which was displaced from this land into Oklahoma. This is contested ground. Even the airspace is propertied; locals have built an airport here, and another fence. At one point during the service, a small airplane flies low overhead, breaking the reverent silence with a motorized snarl.

The line of buses pulls away, and I start to panic as I see them respectfully leaving the site. We’re stuck here! We can’t leave! Where would we go? My body already knows what my mind is only starting to learn: there is power in pain passed down. There is power in a place. No barbed wire fences near us now, no guard towers. And yet.

I look over at Uncle Hiroshi and Auntie Sadako, sitting under the white tents, their heads bent, their gazes calm.

May the injustices and humiliations suffered here never recur.

*

“When I begin to mourn you here, there is a piercing realization that I am not just mourning you. I want to grieve. I think of mourning as clean outward gestures, the rituals that mark a loss. Grief is a wilder, wind-tossed inner emotional landscape.”

The service is interfaith. A Buddhist minister in black robes with wooden prayer beads around his wrist. An incense burner near a folding wooden stand, releasing slow tendrils of smoke. A Christian minister, also in black robes, a stole around his neck. We line up to offer incense, a communal ritual. When I reach the front of the line, I hold my hands together in prayer, and bow. Offer a small pinch of incense into the burner, and bow. Take a few steps back from the burner, bow again. The chanting continues. We stand in the back, saving seats for the elders.

There are silent prayers, too. A candle lighting, one representative from each concentration camp taking turns to light candles on the diorama. And on the ground near the altar, an explosion of color: many of us pilgrims have folded origami cranes at home and on the pilgrimage buses. Volunteers strung them together last night, and the cranes now rustle in the wind.

*

I lost you over thirty years ago when I was ten, to a mystery illness we still can’t even name. Since then, I have spent decades nurturing a hardened grief, glacial and seemingly impenetrable. On some level, I’m surprised at myself being at Tule Lake; before this, I would have avoided anything to do with memorials, with funerals. I have not visited your grave since your death in 1984, and I’m ashamed. Yet here I am on a pilgrimage, on a journey designed to remember and feel a loss. In the heat of this valley, my iceberg resists. I have held onto it for so long.

When I was a college student at Berkeley, the massive AIDS Memorial Quilt visited campus. The Quilt sprawled over the polished floors of both ballrooms inside the student union. I walked slowly around the borders. I heard the names of people who had died read for hours. I don’t cry easily, but a roll call at the Quilt and a physical memorial brought me to tears within minutes. Names, personhood, a physical space to put the grief.

None of these are here. When I begin to mourn you here, there is a piercing realization that I am not just mourning you. I want to grieve. I think of mourning as clean outward gestures, the rituals that mark a loss. Grief is a wilder, wind-tossed inner emotional landscape. I want to feel the loss of you again, even if nothing is left at Tule Lake. After all, isn’t that why we are here? Some cremated ashes of the Tule Lake dead ended up with families; other remains are in the Linkville cemetery some thirty miles away, still others at the camp cemetery. When the camp closed in 1946, the grave markers and tar paper barracks were removed. Dying spaces and living spaces alike. Any buried human remains were plowed under by bulldozers, sent to landfill in construction projects, possibly even moved to the dump across the street. What’s left of the camp graveyard is, as historian Barbara Takei puts it, “a deep and shallow hole.”

I am missing you, and also—the irony—a cemetery.

*

In less than an hour, the air-conditioned buses are scheduled to return. I will climb back onto one of them and leave. The service is a meeting, a greeting, an echoing. Three hundred and thirty-one Japanese Americans died here. Over three hundred and fifty of us pilgrims are here today to honor, to mourn. You died decades after the war, but I can feel that a part of young you lives here still. Remembering that, grief arrives finally: a prickle at the corner of my eyes, a growing pressure in the center of my forehead, the all-too-unfamiliar clenching of the gut, a biting of the lips.

A few years after this trip, in your oldest sister’s scrapbook, I will find a black-and-white photo of you at Tule Lake: an eleven-year-old Japanese American boy and his friend, standing on dust with barracks and Castle Rock in the background. I have never seen this picture before. As a parent of two daughters myself, my chest aches to see you as a child. And now I want to tell that child:

You will leave here.

I will come back for you.

The author’s father, on the right. Photo courtesy of Tamiko Nimura.

About the Author

Photo credit: Josh Parmenter

Tamiko Nimura is an award-winning Asian American creative nonfiction writer and public historian living in Tacoma, Washington. With degrees in English from UC Berkeley and the University of Washington, her training in American ethnic studies prepared her to research, document, and tell BIPOC stories. Her work has appeared in Zócalo Public Square, The Rumpus, Narratively, Full Grown People, and other outlets. She is a regular contributor to Seattle’s International Examiner and Discover Nikkei, a web project of the Japanese American National Museum. Among several public history projects, she is training to be a docent with the Tule Lake Committee. She is working on her third book, a family memoir entitled Pilgrimage.

Read Tamiko’s “Behind the Essay” interview in our newsletter.

This essay was part of a collaboration between OA and the VONA Travel Writers of Color Workshop.

*

Header photo courtesy of the National Park Service.