To the Follower of Chiekh Bamba Whom I Met in Dakar

You had insisted that I look at the postcard until the Chiekh revealed himself to me. I write you to tell you of how, once I returned home, and looked as you encouraged, F., who died recently, came into focus.

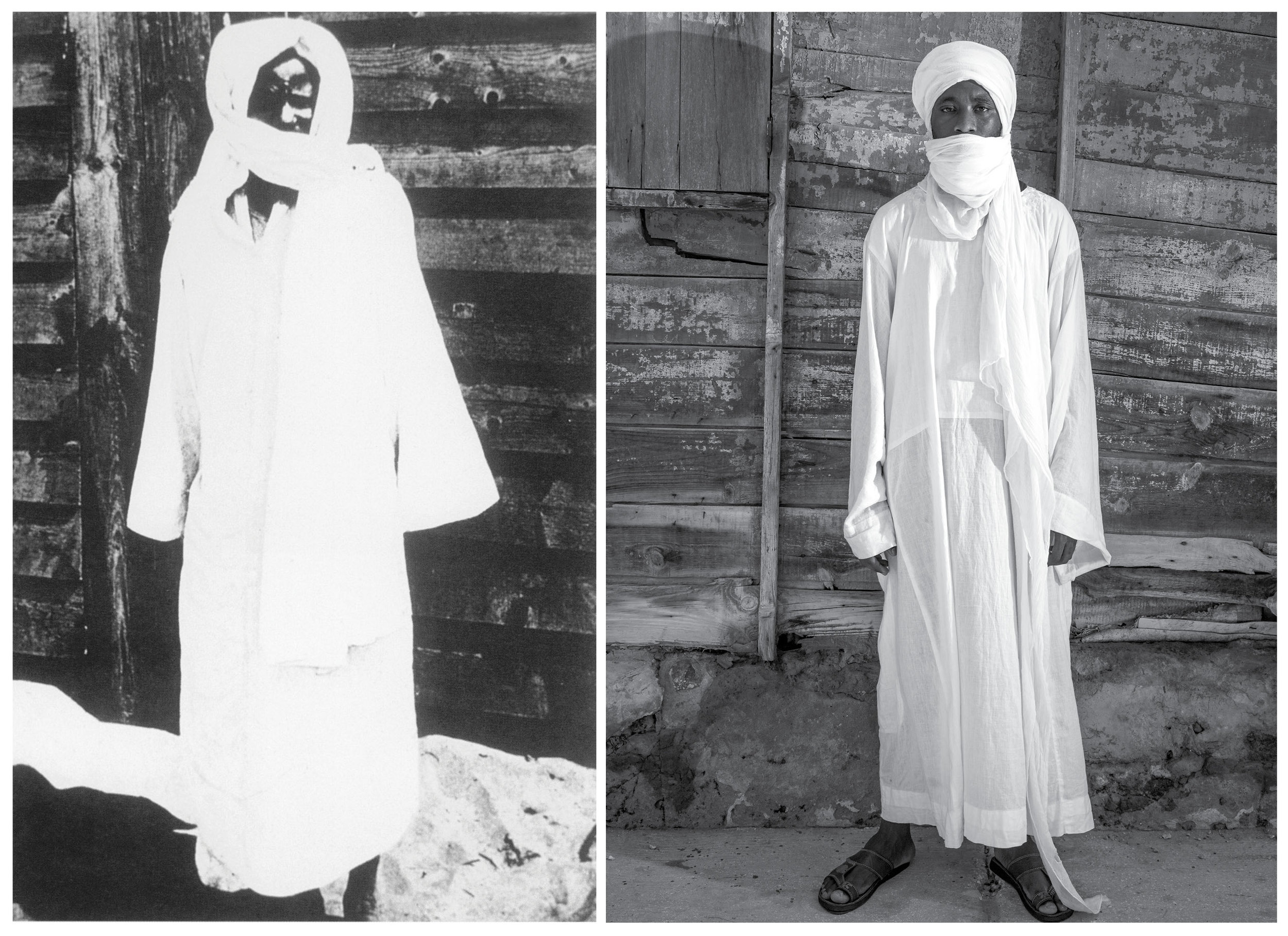

I met you when I arrived in Dakar from Lagos, and you invited me to your house. After our conversation, you handed me a postcard with a photograph of a man whose image I had seen on my drive into the city from the airport. The man’s image was reproduced on drawings, lithographs, murals, glass paintings, almanacs, and postcards. It showed up on walls, windshields, doors, t-shirts, pendants: on any surface against which belief could be affirmed. I have set the postcard above my desk. I look at it intermittently as I write to you. The photograph is of Chiekh Amadou Bamba, a Sufi mystic, and you consider yourself his follower. “I am a Muslim only because of him,” you told me.

F. was a preacher in the Presbyterian Church of Nigeria, and before that an itinerant evangelist for the Scripture Union, a nondenominational Christian organization. I knew him all my life. The Chiekh, as you taught me, told the people of Senegal that as black people they could be good Muslims. He produced a prodigious amount of tracts on the Quran, ritual, work, and the pacifist struggle against the French. He became so highly regarded that the colonial government sent him on exile.

“I like that many before me have looked so devotedly at this photograph that I seem to have learned to venerate secondhand, like a little boy who sees a painting and is convinced all bearded men carry invisible halos.”

Studying the gravitas of the Chiekh on the postcard you gave me, I was reminded of F., of one Sunday while we sang the closing hymn—decked in his cassocks, which had become extra-white from the light that streamed into the chapel, as if to foreshadow a transfiguration. Both men, evoking saintliness, swirl together in my mind’s eye. In writing of one, I slip into writing of the other.

How is it that in looking at the photograph of Chiekh Bamba, I became aware of F.—his death? From its Germanic and Old English roots “awareness” infers watchfulness and vigilance. The state of being aware—like the potency of a presence in the dark. Once I looked at the image as you advised, I began to attend to the image on the postcard, to keep watch. I couldn’t have kept watch over it—what audacity could I have mustered to cast a supervisory net over a culture I entered into as a stranger, one who has never been a Muslim, or Sufi? In taking note of the presence in the photograph, becoming curious about it, I offset an inner alarm, that of grief.

When, later, mindful of F. in his cassock, I considered the possibility of inhabiting the Chiekh’s photograph myself. I returned to Dakar. I wore a similar dress as the Chiekh, posed in front of a similar shack. I mimicked his gravitas, and asked a photographer to record my pose.

Photos courtesy of Emmanuel Iduma

I am attracted by the Cheikh’s poise, a semblance of grace. I like his brilliant white. I like the shadow that falls aslant, and the little heap of fine sand near his feet. I like the 9-shape that his turban forms. I like what might seem like missing hands, and the hint of a leg. You had explained that the missing leg was symbolic of a man straddling two worlds. I like that many before me have looked so devotedly at this photograph that I seem to have learned to venerate secondhand, like a little boy who sees a painting and is convinced all bearded men carry invisible halos.

In order to return to Dakar, I convinced a cultural magazine to commission me to write about the Chiekh. We agreed I would be paid upfront, to enable financial security while I conducted interviews with Islamic scholars and Mourides. The money never came, and I floundered. I did conduct interviews, relying on translators, on chance English words that fell through the cracks of French. But all the writing I did in those four weeks, about the Chiekh, was—believe me and excuse my duplicity—writing about wanting and failing to write about F. It was as if I intended to refract the light from his cassock through the saintliness of the Cheikh.

I remember that when you gave me the postcard, you encouraged me to write about the Chiekh, even though, you warned, “a lot has been written.” I was reminded of Roland Barthes in the last week of his life. He had just completed his lectures, “La Préparation du roman,” and he had announced that he wanted to write a novel—one he will never write—copying out a sketch for it day after day. The sketch comes to eight pages in his slender, sparse handwriting: he has given lectures for two years about the novel he wants to write and it comes to eight skeletal pages. When the subject is vast and vague, a writer traces the outline of the indiscernible.

In fact, the book by Barthes I should think about is his Mourning Diary, fragments written for over two years after his mother died. And Barthes, like me, is unable to talk about his bereavement without the anxiety of not knowing how to properly talk about it, as he writes in one of the entries: “I don’t want to talk about it, for fear of making literature out of it—or without being sure of not doing so—although as a matter of fact literature originates within these truths.”

Of all the miracles attributed to the Chiekh, none is more fabled than one performed aboard the ship deporting him from Senegal to Gabon in 1895, where he would begin his seven-year exile. Kept from praying, he broke free from his chains and cast a prayer mat on the surface of the sea. Then climbed down the ship to affirm his submission. Once he was done he rolled up the mat and returned amidships. During the annual pilgrimage to Touba, the city he founded in Senegal, pilgrims honor this miracle one prayer out of a day’s five, by turning their backs to Mecca, facing the sea. Chiekh Bamba had also authored an estimated twenty thousand mystical verses in Arabic. “My writings are my true miracles,” he wrote.

Writing as a miracle.

In Dakar you told me I must make a pilgrimage to Touba to grasp the extent of his worldview, his spin on Islam, but also to ask God for anything. I was unable to go to Touba, even when I visited your country a second time. When you go on pilgrimage this year, would you pray for me? I am in need of a miracle, to write about F.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Emmanuel Iduma is the author of A Stranger’s Pose, which was longlisted for the 2019 Ondaatje Prize, and The Sound of Things to Come, a novel. He received an arts writing grant from the Creative Capital/Andy Warhol Foundation, for his essays on Nigerian artists. He teaches at the School of Visual Arts, New York. You can find him on Instagram.

Photo credit: Cindy Steiler

Header image by Aliunix