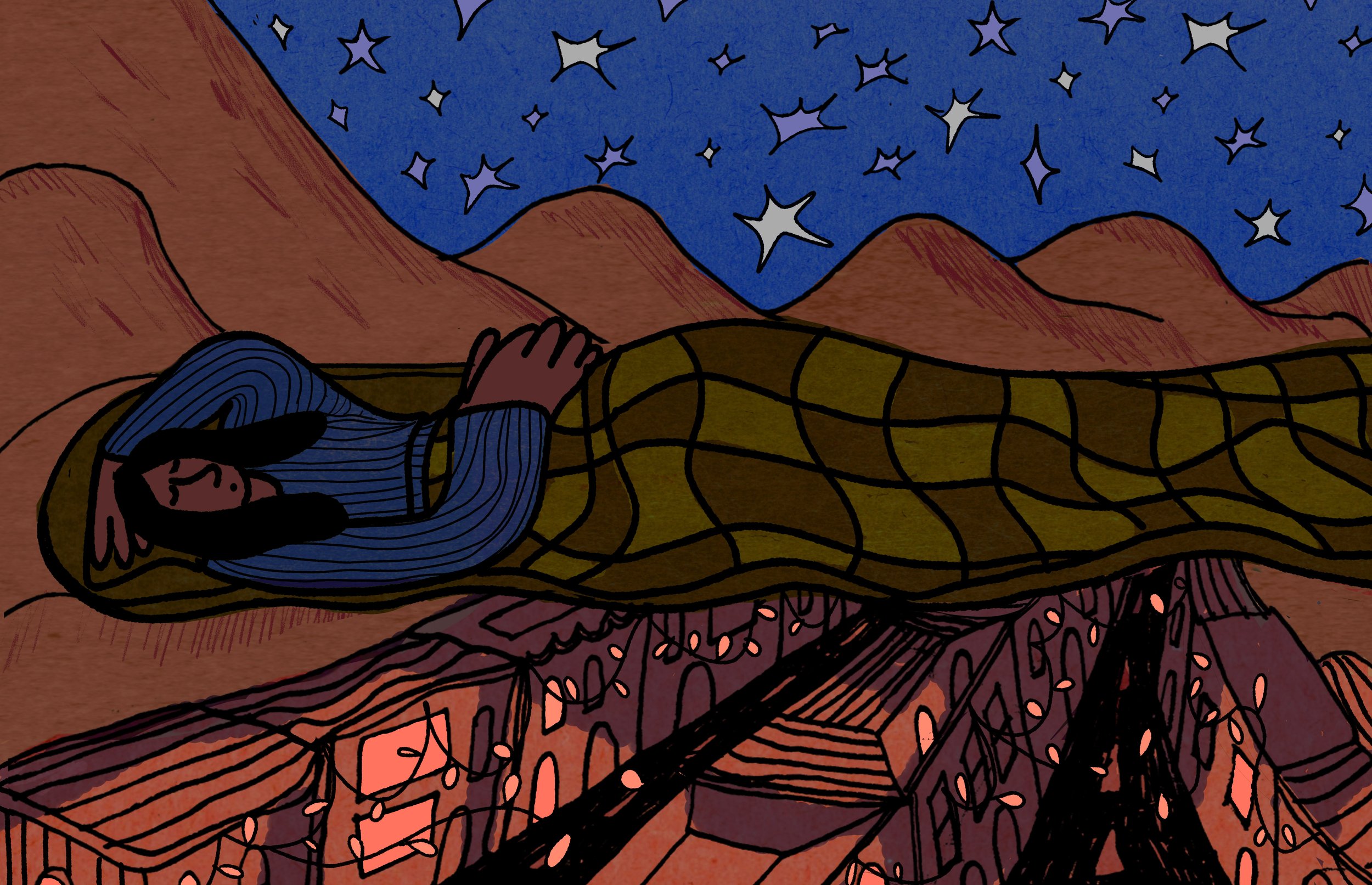

5 a.m. in the Arizona Desert

5 a.m. in the Arizona desert is the safety hour, dark and crisp and still, the blanket of heat not yet descended, the crackle of dust not yet alive.

The sun isn’t up yet, and my daughter is cold. Outside for our morning walk, she shivers, then grins. A desert baby, born on a triple-digit September day, she doesn’t fully understand what it is to feel cold, or what she might do about such a thing. A desert baby, she loves holding ice cubes in her hands and between her teeth, playing with the novelty of an unfamiliar sensation. A desert baby, she is used to hot playground slides on her backside, hot rocks to climb up and over, hot sand sifting through her fingers, hot water spitting out of the coiled hose.

The desert is everywhere, leaving sharp thorns in the soles of our shoes and patches of gritty dust on the edges of the sidewalk, quietly refusing to be muscled out by human development. Ahead of us, a small bunny hops out of the bushes on the side of the street.

It’s a weird neighborhood, ours—not quite city, not quite suburban, one block from a store that sells beer and candy and lotto tickets, two blocks from a farm, three-quarters of a mile from a dried-out riverbed. We live along the bike path, on a long straight road with good sidewalks but few stoplights, where teenagers like to race cars at night. On our corner there is an orange tree, a small collection of landscaped cacti, and a series of pale rocks taller than my daughter.

Tucson is a hub for long-distance cycling. The cyclists move in packs in the morning, whizzing past us, hunched backs sleek with bright spandex suits, their bicycles worth more than our car, their destinations one of the twisty mountain roads that rise above the city, toward the sun.

My daughter is too small to ride a bicycle, or to walk effectively without my hand tugging her into a linear path. I guide her away from the ribs of tall saguaros, away from the needle-sharp ends of agave leaves, away from the cluster of glittering auto glass on the corner of the curb. Already, she understands that she must assess before she touches, that not everything in this world is kind or hospitable. There are no friendly rolling hills or fields of soft grass for her here. The desert is a hard place to be a baby, a hard place to be any kind of person.

Soon, the sun will break the dark seal of the morning. The rhythms of the day will speed up, pick up chaos, start swirling. The birds will twitter louder, the bikes will give way to cars, the creosote in my nose will turn to diesel and hot asphalt, the dust will unsettle. By nine o’clock, it will be too hot to play outside. Our moment of privacy from brightness will end, and with it will go the sense of oasis. In the desert, everything is measured in degrees.

My daughter stumbles. She catches herself with the heel of her hand, steadies herself back to her feet. The concrete sidewalk is cool. My forehead, so accustomed to squinting, feels oddly immobile in the dark, as if I had imagined its ability to move on command.

We whisper to each other, me and my daughter, in these secret mornings, even though we are alone on the road. I feel the twin urges to hurry home and to stretch out our moments, wanting to preserve and hold tight these spots of time. I start and she follows, matching the breath in my voice, the spare chill in the back of our throats.

About the Author

Margo Steines is a native New Yorker, a journeyman ironworker, and serves as mom to a wildly spirited small person. She holds an MFA in nonfiction writing from the University of Arizona and lives and writes in Tucson. Her work was named Notable in Best American Essays 2021 and has appeared in The Sun, Brevity, The New York Times (Modern Love), the anthology Letter to a Stranger: Essays to the Ones Who Haunt Us, and elsewhere. She is the author of The Zoology of Pain, forthcoming in 2023 from W.W. Norton.

Illustration by Amélie Rey Lescure.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure.