3 a.m. in Paris

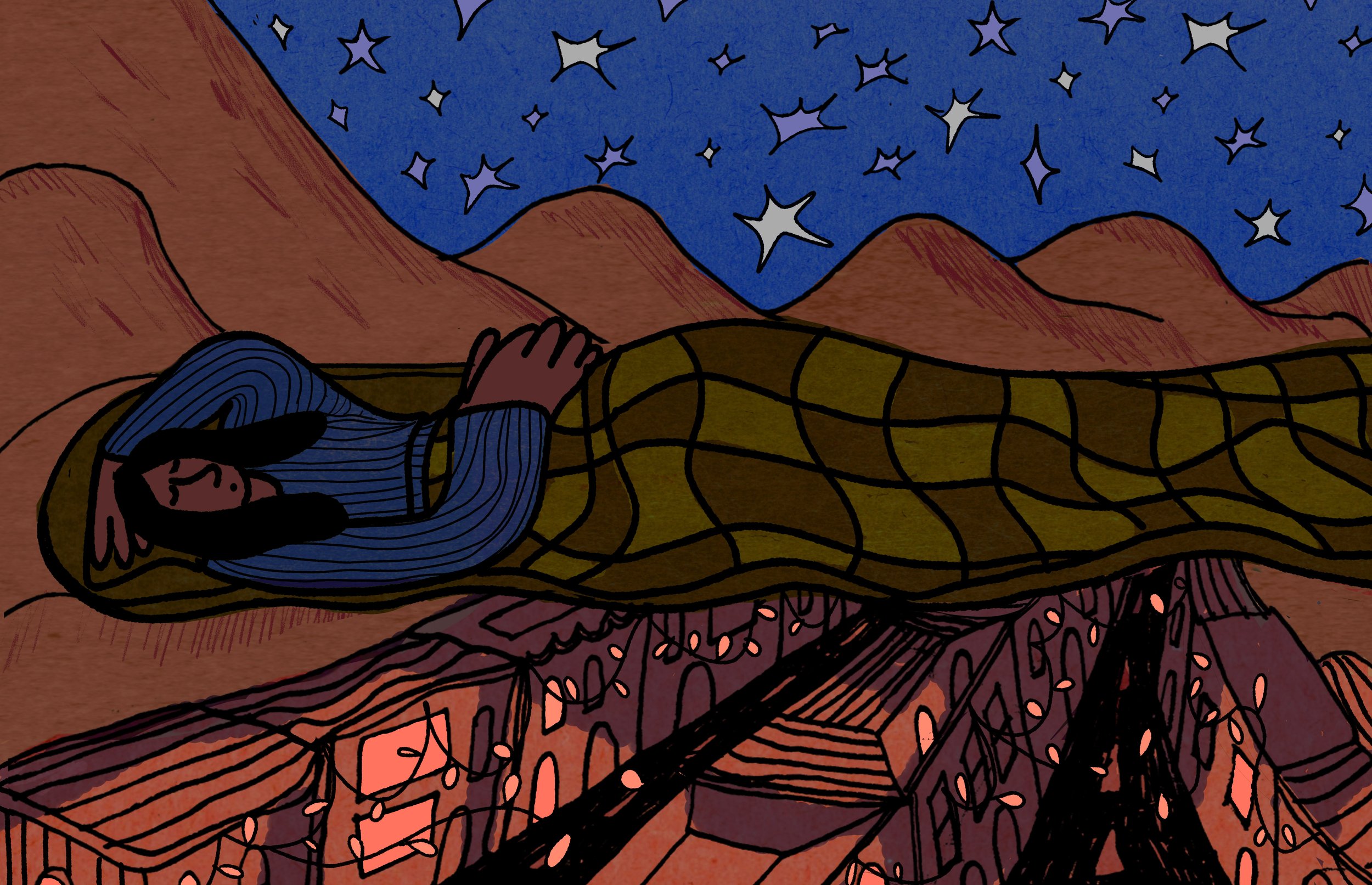

3 a.m. in Paris is when I wear a dress the color of pink roses, tea-length and translucent. It is Bastille Day and I am scurrying to catch the last metro. Earlier tonight, I danced with strangers under fairy lights and a glimmering sky.

I had followed my friend, tripping through dim and narrow streets until she slipped through an unassuming doorframe and we emerged into the light and revelry of an outdoor bar.

We danced. I kissed more men than I could count—they tasted, alternately, like chocolate and gin, tobacco, red wine. At times, I took a break and looked towards other teenagers standing around the dance floor: graceful, giggling girls in short black dresses surrounded by sleepy but strong-looking men. I imagined myself among them: protected, made more beautiful by the radiance of my companions. No, I preferred instead to be made more beautiful by the swishing of my dress, which, when I was alone or dancing, caught the occasional wind and fluttered behind me like wings.

When I bought the dress, I tried to ask the saleswoman whether it was lingerie: C’est pour dormir? Is it for sleeping? No, it’s for daytime. You can wear it to the park. You have to wear a slip underneath—do you know what a slip is?

At the time, I didn’t recognize the French word. What I did know was that the dress wasn’t entirely transparent. Before putting it on, I held it up against my room’s white wall under the unforgiving yellow beam of a flashlight. Not a speck of white shone through: the dress was festive without a slip.

That night, at the metro station, the deep, coffee brown of the wooden bench beneath me shows dark through the dress. My body, too. I pull at a loose thread and notice, also tugging at my skirt, another hand. Pale, hairy, deep-creased, male. He lies wrapped in an old blanket on the bench next to mine, his other hand jerking beneath the cover. I don’t see his face. His hold on me is loose, and if I were to shift my weight, he’d release his grip. My heart cools, its beat slows nearly to a stop. We are alone. If I move, then I acknowledge that something I would never choose is happening to my body. To me. But unmoving, I can pretend it is not me: I am not my dress. The fabric isn’t part of me, to keep or to give. I don’t move until he sighs. The approaching train illuminates the tiled walls in shades of sunrise. I rise and sigh, too. Everything smells sweet like wine, and the tunnel is full of light.

In the train’s sickly, green-white light, I’m a germ under a microscope. Wearing the rose dress and no longer drunk, I’m too afraid to fall asleep. At my stop, I step from the warm station into the chilly black night, and see, in the pink shadow on the sidewalk (moonlight shining through my dress), a man’s silhouette.

At the corner I cut left and run. The tiers of the dress are useless wings. The man will snatch on to the billowing fabric and pull and my dress will tear and tear to shreds and I will be naked, brown skin bare under the jaundiced moon.

I reach the gate of my house at the same time as the man who shadows me. Est-ce que vous avez de l’eau? What? Water? I say, struggling with French, the cumbersome key, the iron door. I am stammering. My heart, too. J’ai dit, avez-vous de l’eau? He curls his hand around an imaginary object, lifts his head, and moves the object back and forth, to and from his mouth. I shake my head, and he starts shouting, words about women I pretend not to know—t’es conne, t’es une salope—and finally the door gives: I slip in.

About the Author

Coryna Ogunseitan is a writer from Orange County, California. Currently they live in the Bay Area where they are pursuing a PhD in Anthropology at UCSF. Coryna also holds an MSW from UC Berkeley and has worked in community mental health. Her work has also appeared in Electric Literature. When not reading or writing, Coryna can be found anywhere outdoors—hiking, gardening, or at the beach.

Illustration by Amélie Rey Lescure.

Edited by Aube Rey Lescure.