1 p.m. in Binbrook

1 p.m. in Binbrook is humming with prayer. I overhear the apple tree in my Sito’s backyard swelling with unpicked fruit, existing wildly outside of human consumption. The bark of a neighbor’s dog harmonizes a tractor mowing grass crops past her property. Wind rustles a tarp strewn across an untouched above-ground pool in the adjacent backyard. I imagine it covering thick, jello-like water, solidifying in its concrete container. I imagine what I can’t hear, the algae and bug colony propagating against the tarp.

Gnats and mosquitoes buzz around my skin and the inside of my ears. I braid my hair so they won’t get caught like they used to as a kid, when Sito would have to gently and slowly drag them out as I squirmed and whined with anxiety, feeling full of small creatures. The air bloats with their buzzing and the heat—reliable August sounds, year after year. When I walk towards the field, my bare feet sting with dandelion pricks. I am forced to learn my lesson or accept my role in this natural economy. Paying my dues, I stay barefoot and without bug spray. I warn my sister of the sting—without their bright yellow flowers the pricks are concealed in the grass—before she reminds me that she’s kept her shoes on.

I wander to the house filled with cousins, aunts, and uncles. Inside, heat crystallizes like honey. My Sito sits at her kitchen table as I ask her to tell me stories about my Sido, about Palestine, about her life, about Bay Ridge and Syracuse, and her parents. I slip my phone onto the table to record her as she speaks; for her memories to become mine, and my children’s, and my children’s children’s.

We look through the kitchen window at the backyard. The nearby farmland is being swept up rapidly by developers. I imagine suburban sprawl layered over the field and build a mental shrine to the land in hopes of protection. This is the only view from childhood I can return to, a consequence of restless parents who have moved almost every seven years since I was born. While I watched three homes painfully boxed up and emptied, and part of me with them, Sito’s house remains full.

A small reservoir sits beyond a thin strip of natural forest behind this home. Over the years, the reservoir has become a mecca, a walk I must take at least once a year to make sure it’s still there, that it hasn’t dried out. I worry if we don't see it and call into it, throw rocks and visit it, the reservoir will be taken away by some higher power. And so, in ritual superstition and self-preservation, I go.

About the Author

Danielle Bettio has published work and performed under various pseudonyms. She supports and organizes socialist movement against capitalism and U.S. imperialism (free Palestine), and is an acupuncture student, herbalist + community healthcare enthusiast. If she had to choose between morning and night, both notably loved, she would pick early morning for a slow start to the day.

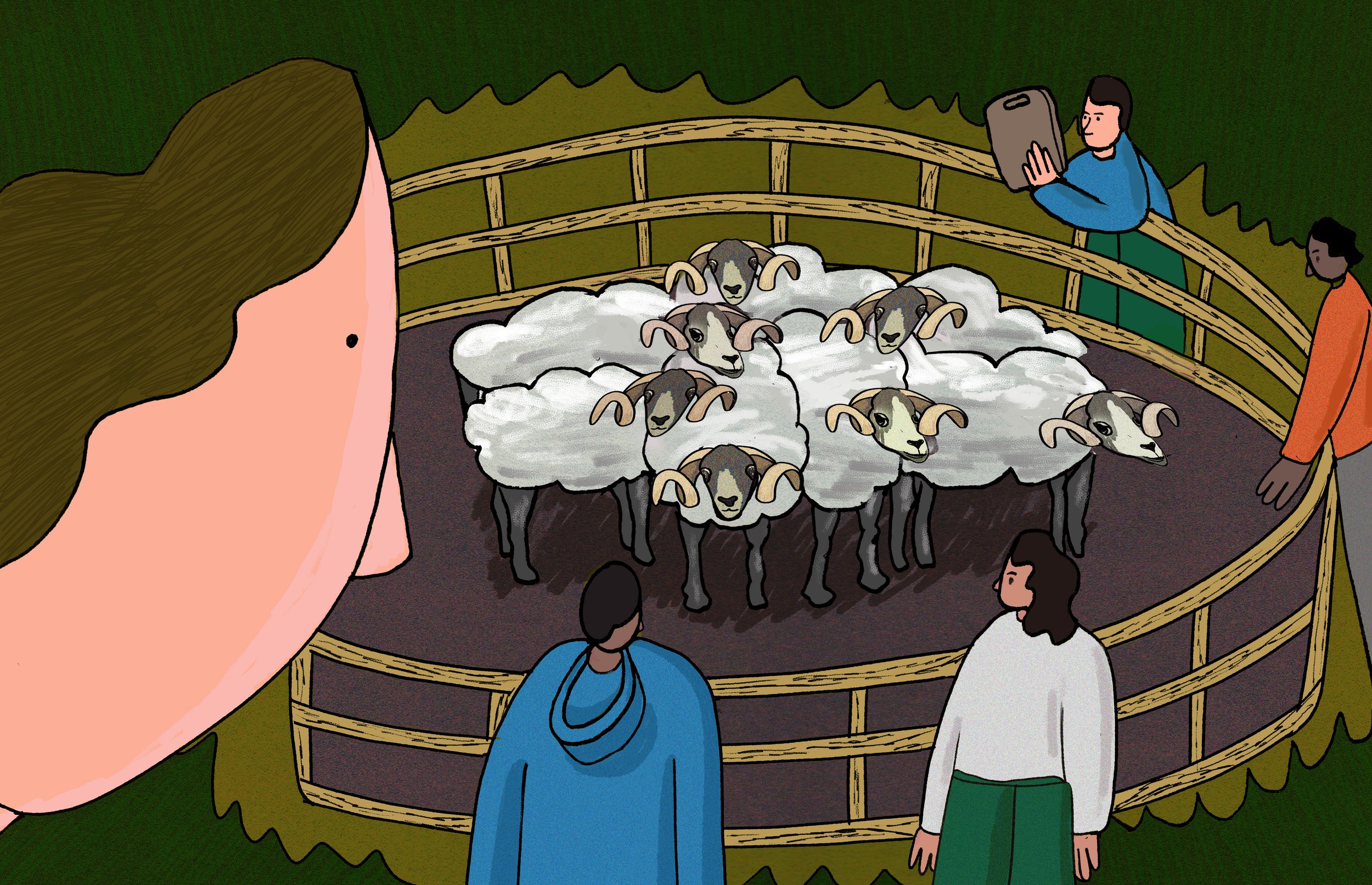

Illustration by Jane Demarest.

Edited by Tusshara Nalakumar Srilatha.